In August 1835, readers of a New York newspaper awoke to astonishing news.

In August 1835, readers of a New York newspaper awoke to astonishing news.

Astronomers had discovered life on the Moon.

Not just life — but civilization.

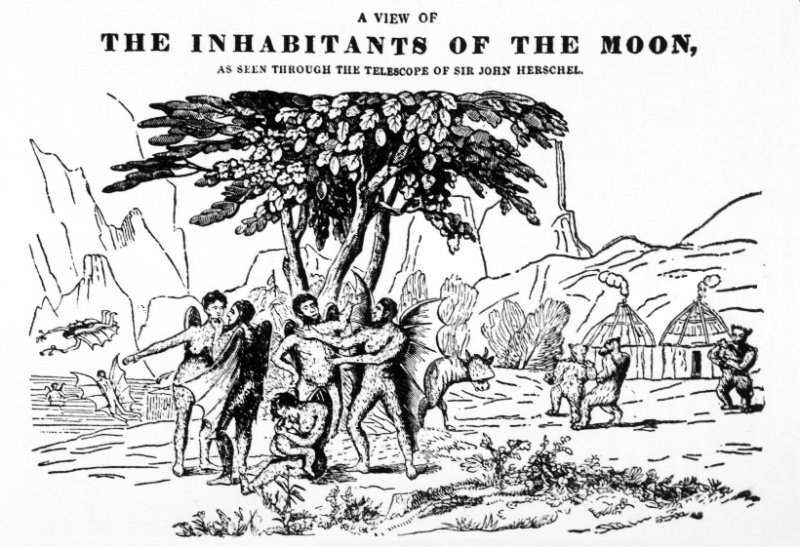

There were forests of crimson flowers. Blue unicorn-like animals grazing in lunar valleys. Bipedal beavers that built temples. And most sensationally of all: winged humanoids — “Vespertilio-homo,” or bat-men — soaring beneath jagged cliffs of amethyst.

The source was not rumor.

It was science.

Or so it appeared.

The articles were published by The Sun, a rapidly growing New York newspaper, and attributed to the respected British astronomer Sir John Herschel. The discoveries were said to have been made from a powerful new telescope in South Africa.

For six days, New York City — and eventually the English-speaking world — was captivated.

It was all fiction.

This was The Great Moon Hoax of 1835, one of the most successful media deceptions in history — a masterclass in storytelling, scientific plausibility, and the power of public hunger for wonder.

The Age of Astronomical Fever

The 1830s were a time of intense fascination with science.

Astronomy, in particular, was capturing the imagination of the public. Telescopes were improving. Discoveries about planets and comets were regularly making headlines. The idea that other worlds might harbor life was not absurd — it was actively debated.

Speculation about lunar inhabitants had circulated for decades. Philosophers and writers wondered whether the Moon, with its visible craters and mountains, might sustain some form of civilization.

Science was expanding.

So was imagination.

The Rise of The Sun

The hoax emerged from the bustling newsroom of The Sun, founded in 1833 by Benjamin Day.

Unlike elite newspapers that catered to the wealthy, The Sun targeted working-class readers. It cost only a penny — revolutionary at the time — and relied on sensational stories to boost circulation.

The “penny press” had transformed journalism.

To survive, newspapers needed readers.

To get readers, they needed spectacle.

Enter Richard Adams Locke.

The Architect of the Hoax

Richard Adams Locke, a reporter for The Sun, was almost certainly the author of the Moon series.

He crafted the story as a series of six installments beginning on August 25, 1835.

The articles claimed to be reprinted from a supplement to the Edinburgh Journal of Science, a legitimate publication.

They described, in elaborate technical detail, the construction of an enormous telescope at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa.

This telescope — impossibly advanced — supposedly allowed Herschel to observe lunar life in breathtaking clarity.

The tone was scientific, methodical, and convincing.

And readers believed.

The First Reports

The initial article focused on the telescope itself — a marvel of engineering with a 24-foot lens and unprecedented magnification.

Locke described:

-

A hydro-oxygen illumination system.

-

A magnifying power capable of viewing objects on the Moon as clearly as objects on Earth.

-

Technical specifications dense enough to deter skepticism.

It read like legitimate science journalism.

Only gradually did the discoveries escalate.

Lunar Landscapes

Soon, readers learned of breathtaking lunar vistas.

There were:

-

Vast sapphire seas.

-

Golden plains.

-

Amethyst mountains rising miles high.

Vegetation flourished — crimson blossoms and exotic trees.

Animals roamed freely.

The descriptions blended Romantic poetry with scientific authority.

The Moon was no longer a barren rock.

It was a living Eden.

The Bat-Men

Then came the most sensational revelation.

The astronomers had observed humanoid creatures about four feet tall, covered in short copper-colored hair, with membranous bat-like wings.

They walked upright.

They built temples.

They appeared intelligent.

The term “Vespertilio-homo” was coined.

These lunar beings were depicted as peaceful, social, and possibly spiritual.

For readers in 1835, the concept was electrifying.

Life beyond Earth was not merely possible — it was confirmed.

Public Reaction

New York was enthralled.

Circulation of The Sun soared.

Other newspapers reprinted the articles.

Debate erupted in salons and taverns.

Clergy discussed theological implications.

Scientists expressed cautious intrigue.

Few readers questioned the story’s authenticity.

The attribution to Herschel — a respected astronomer and son of William Herschel, discoverer of Uranus — lent credibility.

And communication delays meant verification was impossible in real time.

South Africa was months away by ship.

When Doubt Emerged

Skepticism eventually surfaced.

Some astronomers quietly noted that the described telescope defied physical laws.

Others questioned the absence of corroboration from Europe.

But the hoax was not immediately exposed.

It simply faded.

After the sixth installment, The Sun abruptly stopped publishing lunar discoveries.

No dramatic confession followed.

The public gradually realized they had been duped.

Why It Worked

The Great Moon Hoax succeeded because it blended three powerful elements:

1. Scientific Plausibility

The articles were dense with technical jargon, mimicking authentic scientific reporting.

2. Authority

Attributing the discoveries to Herschel made them believable.

3. Narrative Escalation

Each installment grew more spectacular, building anticipation.

Locke understood that readers wanted to believe.

The Moon, long a symbol of mystery, became a stage for wonder.

Was It Satire?

Historians debate Locke’s intention.

Some argue he intended the hoax as satire — a critique of speculative astronomy and popular gullibility.

Others see it as purely commercial — designed to boost sales.

Locke himself later suggested it was meant to mock contemporary astronomical theories about extraterrestrial life.

But satire and sensationalism often coexist.

Whatever the motive, the result was circulation gold.

Herschel’s Reaction

Sir John Herschel was reportedly amused — not outraged — when he learned of the hoax.

He did not sue.

He did not publicly rage.

In an era before instantaneous communication, reputational damage was limited.

Still, the episode underscored the vulnerability of scientific authority to media manipulation.

The Birth of Modern Media Sensation

The Great Moon Hoax is often cited as one of the first major examples of modern “fake news.”

It demonstrated how:

-

Mass media could shape belief.

-

Authority could be fabricated.

-

Public enthusiasm could override skepticism.

It foreshadowed later media frenzies — from yellow journalism to viral internet hoaxes.

The Cultural Legacy

The hoax inspired:

-

Stage plays

-

Illustrations of bat-men

-

Satirical commentary

It cemented The Sun’s place in newspaper history.

And it left a lingering cultural question:

How easily do we believe what we want to believe?

The Moon After the Hoax

Ironically, the real scientific exploration of the Moon in the 20th century would prove it lifeless.

When humans finally landed there in 1969, they found dust, rock, and silence.

No forests.

No temples.

No bat-men.

But the romance of lunar life had already been seeded.

The Great Moon Hoax did not kill curiosity.

It amplified it.

Final Reflections: The Power of Wonder

The Great Moon Hoax was not merely a trick.

It was a mirror.

It reflected a society eager for discovery.

Hungry for cosmic connection.

Ready to believe that humanity was not alone.

For six dazzling days in 1835, New York’s readers imagined a universe teeming with life.

They pictured winged beings gliding under alien skies.

And even after the truth emerged, the thrill lingered.

The hoax endures not because it fooled people — but because it reminds us how powerful stories can be.

The Moon remained barren.

But for one extraordinary week, it was alive with possibility.

And sometimes, that possibility is as enduring as fact.