On the evening of October 17, 1814, in the crowded parish of St. Giles in London, something ruptured inside a brewery.

On the evening of October 17, 1814, in the crowded parish of St. Giles in London, something ruptured inside a brewery.

At first it was just a crack — a splitting sound in iron.

Then came a roar.

A massive wooden vat filled with fermenting porter gave way, releasing a tidal wave of beer into one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city. The force shattered surrounding tanks, creating a chain reaction that unleashed nearly 320,000 gallons of beer into the streets.

Homes collapsed.

Walls caved in.

Families were trapped.

Eight people died.

This was the London Beer Flood, a disaster so strange it sounds like urban legend — and yet it was painfully real. It was industrial Britain colliding with poverty, infrastructure weakness, and the simple physics of liquid under pressure.

And like many tragedies of the Industrial Age, it was deemed “an act of God.”

St. Giles: London’s Hidden Underside

Early 19th-century London was a city of stark contrasts.

Grand townhouses and royal parks stood only streets away from cramped slums known as “rookeries.” St. Giles was one of the most notorious.

It was overcrowded.

It was impoverished.

It was poorly built.

Families crammed into flimsy brick homes, often constructed hastily and without structural integrity. Sanitation was poor. Disease was common.

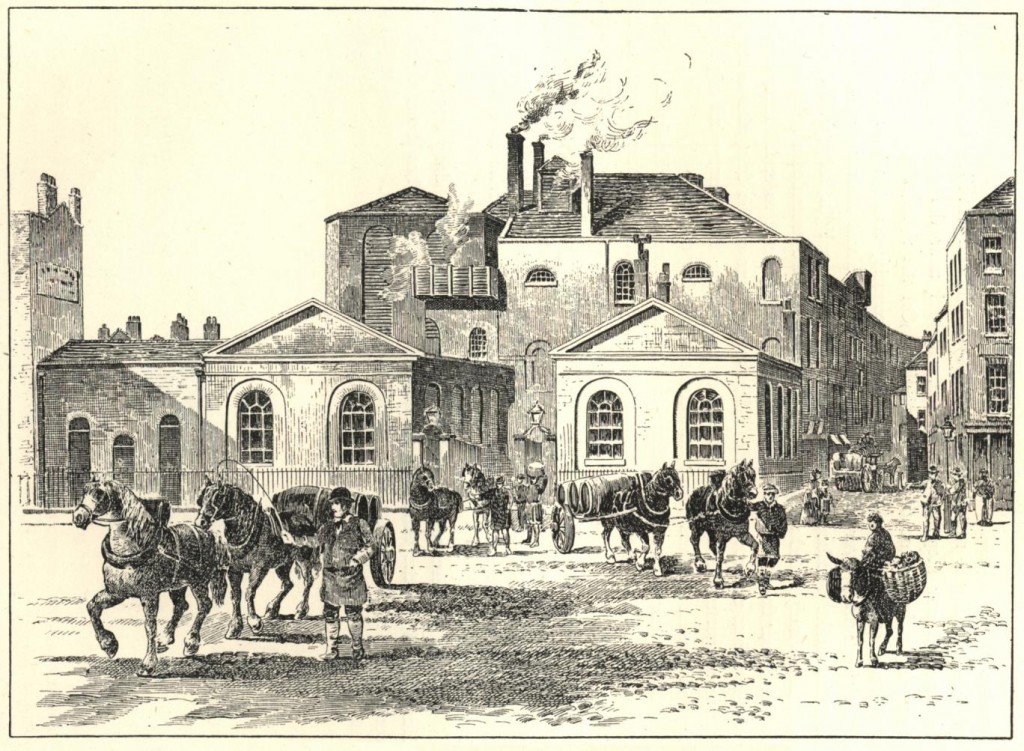

And towering over part of the neighborhood was the Meux & Company Brewery, a massive industrial operation producing dark porter beer.

The brewery’s vats were enormous — some as tall as four-story buildings — built from wood and reinforced with heavy iron hoops.

They were engineering marvels.

They were also potential bombs.

The Vat That Failed

On October 17, 1814, one of the brewery’s largest vats — holding approximately 135,000 gallons of porter — began to show signs of stress.

Earlier in the day, an employee noticed that one of the iron hoops encircling the vat had slipped.

Such failures were not uncommon.

The brewery had experienced minor hoop failures before without catastrophe.

No one considered it urgent.

Around 5:30 p.m., the vat burst.

The Chain Reaction

When the first vat ruptured, the pressure release was explosive.

The collapsing structure smashed into adjacent vats, triggering a domino effect.

Within moments, several enormous containers split apart.

The combined total of released beer reached approximately 320,000 gallons — the equivalent of nearly a million modern pints.

The liquid surged outward with incredible force.

This was not a gentle spill.

It was a tidal wave.

A Wave Through the Rookery

The beer burst through the brewery walls and into the surrounding streets of St. Giles.

Witnesses described a wall of liquid up to 15 feet high.

Homes crumbled instantly.

Brick walls collapsed.

People were swept off their feet.

The beer flooded basements — which in St. Giles were often living quarters for the poorest residents.

Inside one home, a mother and daughter were having tea.

The flood tore the building apart.

They were killed instantly.

The Victims

Eight people died in the disaster.

Among them:

-

A young girl attending a wake

-

A pregnant woman

-

Several children

-

Adults trapped beneath rubble

The irony was brutal.

The beer itself was not toxic.

But its force destroyed fragile housing and buried residents under debris.

In a neighborhood where buildings were already structurally unsound, the flood proved catastrophic.

The Aftermath: Chaos and Curiosity

In the hours following the flood, crowds gathered.

Londoners were drawn by the absurdity of it.

Reports suggest some residents attempted to collect beer from the streets in buckets and pots.

Though stories of drunken chaos circulated, historians debate how widespread such behavior truly was.

What is certain is that the neighborhood was devastated.

The smell of porter lingered.

Debris filled alleys.

Families mourned.

The Brewery’s Defense

The Meux Brewery faced public scrutiny.

Was this negligence?

Poor maintenance?

Industrial recklessness?

An official inquest was held.

The verdict?

The disaster was ruled an “Act of God.”

The brewery was not held criminally responsible.

No compensation was required beyond minimal funeral costs.

The reasoning reflected the era’s attitude toward industrial accidents.

Catastrophes were often considered unavoidable consequences of progress.

Why the Vat Failed

The brewery’s vats were constructed of massive wooden staves held together by iron bands.

As fermentation occurred, gases built pressure inside.

The design relied on constant structural integrity of the hoops.

When one iron band slipped, the load distribution shifted.

The wooden structure could not contain the pressure.

Once one vat collapsed, its impact shattered others nearby.

It was a textbook case of structural failure under dynamic load.

But in 1814, industrial engineering standards were still evolving.

Industrialization Without Regulation

The London Beer Flood occurred during Britain’s Industrial Revolution.

Factories were expanding.

Production scaled upward.

Urban density increased.

Safety standards lagged behind innovation.

Large industrial installations often sat directly adjacent to residential areas.

Working-class neighborhoods bore the risk.

When failure occurred, it was often the poor who suffered most.

The Economic Impact

The Meux Brewery claimed significant financial loss.

Insurance covered much of the damage to the brewery.

But the human cost was borne largely by St. Giles residents.

No major reform followed immediately.

Beer production continued.

Large vats remained in use for decades.

Public Fascination

The disaster captured the public imagination.

Newspapers across Britain reported on the “beer deluge.”

Some accounts sensationalized the event, describing rivers of ale and intoxicated survivors.

It became part of London lore.

But behind the spectacle lay stark inequality.

It was a tragedy rooted in where the brewery was placed — and who lived nearby.

A Disaster of Its Time

The Beer Flood reflects a pattern common in 19th-century industrial cities:

-

Massive infrastructure

-

Limited oversight

-

Dense poverty

-

Reactive, not preventative, governance

Only later would building codes and industrial safety regulations become widespread.

In 1814, industry moved faster than accountability.

The Physical Reality of Liquid Force

To modern eyes, 320,000 gallons might sound dramatic but manageable.

It is not.

Liquid under pressure becomes kinetic energy.

When released suddenly, it carries force comparable to flooding rivers.

Even though beer is lighter than water, its volume and velocity were sufficient to demolish weak structures.

This was physics, not fantasy.

The Changing Landscape

The Meux Brewery eventually closed in 1921.

Today, the site near Tottenham Court Road is occupied by modern buildings.

Few traces remain of the disaster.

A plaque marks the location.

The memory persists more in anecdote than in architecture.

Why It Endures in Memory

The London Beer Flood endures because it is surreal.

Beer — associated with celebration and leisure — became an instrument of destruction.

The name itself sounds like satire.

But like many strange disasters, its absurdity masks deeper truths.

It reveals how industrial ambition can overlook vulnerable communities.

Not the Only Unusual Flood

History contains other strange liquid disasters:

-

Molasses in Boston (1919)

-

Wine floods in Europe

-

Industrial chemical spills

Each reflects the same pattern:

Mass production meets structural failure.

And ordinary people pay the price.

Final Reflections: When Industry Overflows

The London Beer Flood was not caused by malice.

It was caused by:

-

Overconfidence in engineering

-

Insufficient oversight

-

The proximity of industry to poverty

Eight people died beneath collapsing brick and rising ale.

Their story reminds us that progress without precaution carries risk.

The vats burst.

The beer surged.

The streets filled.

And for one strange, terrible evening, London drowned in porter — not in metaphor, but in fact.

History remembers the name.

But the flood was no joke.

It was a wave of industry crashing into fragile lives — and leaving silence in its wake.