In the late 19th century, London was the largest city in the world.

In the late 19th century, London was the largest city in the world.

New York was racing to catch it.

Paris, Berlin, Chicago — all swelling with industry and ambition.

Steam powered factories. Telegraph wires stitched continents together. Skyscrapers began to rise.

And beneath it all — coating the streets, clogging the gutters, and baking in the sun — was horse manure.

Tons of it.

By the 1890s, major cities faced what newspapers and urban planners openly described as a looming catastrophe. Some experts predicted that within 50 years, London would be buried under nine feet of horse manure. New York’s streets were already described as impassable in summer heat and lethal in winter slush.

It was not satire.

It was math.

And it was terrifyingly logical.

This was the Great Horse Manure Crisis — a moment when modern civilization nearly choked on its own transportation system.

A City Powered by Horses

Before automobiles, before subways, before electric streetcars, cities moved on hooves.

Horses powered:

-

Taxis (called hansom cabs)

-

Omnibuses

-

Delivery wagons

-

Fire engines

-

Private carriages

-

Freight haulers

In 1890, New York City alone had approximately 100,000 horses working daily.

London had a similar number.

Every single one of them produced waste.

A lot of it.

The Math of Manure

A single working horse produces roughly:

-

15 to 35 pounds of manure per day

-

About a gallon of urine

Multiply that by 100,000 horses.

New York generated an estimated 2.5 million pounds of manure every day.

That’s over 1,200 tons daily.

And it didn’t politely disappear.

It piled up.

Mountains in the Streets

In summer, manure dried into fine dust.

Carriages crushed it into powder, which blew into:

-

Open windows

-

Food markets

-

Lungs

Respiratory diseases were common.

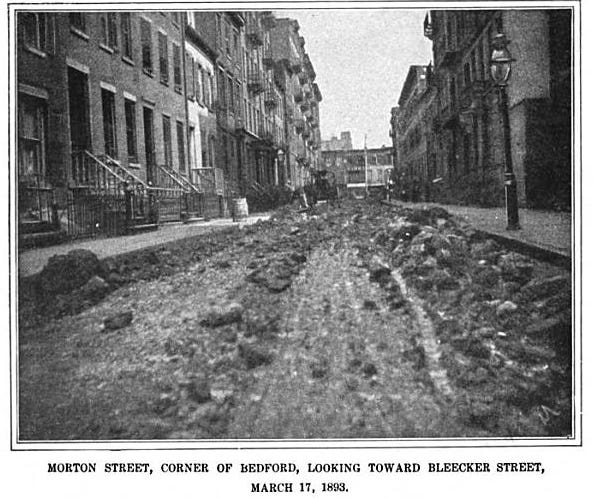

In winter, manure mixed with rain and snow, creating a viscous sludge that coated streets and seeped into basements.

Newspapers described intersections as impassable.

Pedestrians waded ankle-deep in filth.

Street sweepers struggled to keep pace.

And then there were the dead horses.

The Dead Horse Problem

Horses were overworked.

They collapsed in harness.

They slipped on cobblestones.

They died in the streets.

In New York in the 1880s, it’s estimated that around 15,000 horses died annually.

Removing an eight-hundred-pound carcass was not quick.

Dead horses often lay in the street for hours — sometimes days — bloating, attracting flies, and blocking traffic.

The smell was overwhelming.

Cities weren’t just dirty.

They were biologically hazardous.

Disease and Flies

Manure is not merely unpleasant.

It breeds flies.

In the 19th century, flies were a major vector for disease. They spread typhoid, dysentery, and other infections by landing on manure and then on food.

Summer brought waves of illness.

Children died at alarming rates.

Doctors increasingly recognized the link between urban filth and public health crises.

Horse manure was not just an aesthetic problem.

It was a medical one.

The 1894 Panic

In 1894, The Times of London published a grim prediction: if population growth and horse usage continued at current rates, London would be buried under nine feet of manure within 50 years.

Urban planners convened conferences to discuss solutions.

In New York, officials openly debated the impending catastrophe.

The logic was relentless:

More people → more transport → more horses → more manure.

The growth curve seemed unstoppable.

Cities were expanding.

Industry demanded movement.

There was no alternative.

Attempts at Solutions

Municipal governments tried various approaches:

-

Hiring more street sweepers

-

Regulating manure removal

-

Encouraging farmers to collect manure for fertilizer

But supply outpaced demand.

Farmers once valued manure as fertilizer.

By the 1890s, urban production exceeded agricultural need.

The excess had nowhere to go.

In some areas, manure was piled into mounds as tall as 60 feet.

It became part of the skyline.

The Environmental Toll

Rain washed manure into waterways.

Rivers became polluted.

Fish died.

Drinking water sources were contaminated.

The urban ecosystem strained under the load.

Yet horses remained indispensable.

Without them, cities would stop moving.

Why Not Just Fewer Horses?

The problem was structural.

There was no viable alternative to horse power.

Steam engines were too bulky for urban streets.

Electric systems were in their infancy.

Bicycles were limited in cargo capacity.

Cities were trapped by their own infrastructure.

Progress had created a bottleneck.

The Irony of Progress

Industrialization was accelerating.

Railroads connected continents.

Factories mechanized production.

But within city limits, transportation remained medieval.

Every modern building required horses to deliver materials.

Every store depended on horse-drawn wagons.

The more modern the city became, the more manure it generated.

It was an absurd paradox.

A Crisis That Solved Itself

Here’s the twist.

The Great Horse Manure Crisis did not end because of sanitation reform.

It ended because of technology.

In the early 20th century, three innovations converged:

-

The electric streetcar

-

The subway

-

The automobile

Henry Ford’s Model T, introduced in 1908, made personal vehicles affordable.

Within a decade, horse populations in major cities plummeted.

By the 1920s, horses were largely gone from urban streets.

The manure vanished with them.

A New Set of Problems

Of course, the automobile introduced its own crises:

-

Air pollution

-

Oil dependency

-

Traffic congestion

-

Carbon emissions

But in 1900, cars looked like salvation.

They didn’t defecate.

They didn’t die in the street.

They didn’t breed flies.

Cities exhaled.

The manure crisis evaporated almost overnight.

The Blind Spot of the Future

Urban planners in 1894 could not imagine the automobile revolution.

Their projections assumed the future would resemble the present — only more so.

They extrapolated existing trends linearly.

They did not account for disruptive innovation.

This is what makes the Great Horse Manure Crisis so fascinating.

It wasn’t stupidity.

It was incomplete imagination.

A Lesson in Forecasting

The manure crisis is often cited in discussions of technological forecasting.

It reminds us that:

-

Current problems may be solved by unforeseeable inventions.

-

Linear projections often fail in dynamic systems.

-

Crises can vanish when paradigms shift.

In 1894, the idea of millions of gasoline-powered vehicles seemed as improbable as flying machines.

Within 20 years, both existed.

The Smell of Change

For decades, urban life had a distinct aroma.

Visitors to New York or London commented frequently on the stench.

When horses disappeared, cities smelled different.

Cleaner.

Less organic.

More industrial.

The disappearance of manure marked a sensory shift as much as a technological one.

The Hidden Cost of Horse Power

Horses also required enormous resources:

-

Feed production consumed vast agricultural land.

-

Stables occupied valuable urban space.

-

Veterinary care and labor added expense.

Switching to mechanical power freed land and labor for other uses.

It accelerated modernization.

A Crisis We Barely Remember

Today, the Great Horse Manure Crisis is a historical footnote.

We joke about it.

We cite it in urban studies.

We forget how serious it felt.

But in 1894, it was existential.

Cities truly feared being buried.

It was a reminder that even mundane systems — like transportation — can produce overwhelming consequences.

Final Reflections: The Weight of the Present

The Great Horse Manure Crisis teaches a humbling lesson.

Every era believes its current systems are permanent.

In 1890, horses seemed eternal.

In 2024, cars feel entrenched.

But infrastructure evolves.

What feels inevitable today may be obsolete tomorrow.

In the late 19th century, cities stood ankle-deep in filth, convinced the future was a mountain of manure.

Instead, the future arrived on rubber tires.

The streets cleared.

The piles vanished.

And civilization moved on.

The crisis that once seemed insurmountable dissolved — not because planners solved it directly, but because innovation changed the question entirely.

History doesn’t always solve problems head-on.

Sometimes it simply invents something new — and leaves the manure behind.