On November 12, 1970, the Oregon coast became the site of one of the strangest government decisions in American history.

On November 12, 1970, the Oregon coast became the site of one of the strangest government decisions in American history.

A 45-foot, eight-ton sperm whale had washed ashore near Florence, Oregon. It was dead. Bloated. Beginning to rot. And emitting a smell that residents described as something between diesel fuel, spoiled meat, and the end of the world.

Local authorities faced a practical problem: how do you dispose of an eight-ton carcass decomposing in public view?

Their solution seemed simple.

They would blow it up.

What followed would become legend — a perfectly preserved case study in bureaucratic confidence, underestimated physics, and the stubborn unpredictability of nature.

This is the story of the Exploding Whale Incident — the day 20 sticks of dynamite rained blubber from the sky.

The Whale Arrives

The whale came ashore quietly.

It was a massive sperm whale, roughly 45 feet long and weighing an estimated eight tons. Like many whales that strand themselves along coastlines, it had likely died offshore and drifted until the tide carried it in.

By the time it settled onto the beach near Florence, it was already in an advanced state of decomposition.

And decomposing whales are not subtle.

As gases build inside the carcass — methane, hydrogen sulfide, and other byproducts of decay — the body swells. The skin stretches tight. Internal pressure rises. The smell becomes overwhelming.

Residents reported that the stench carried for miles.

This wasn’t just unpleasant.

It was urgent.

A Practical Problem

In 1970, there were no clear protocols for disposing of massive marine mammals in public areas.

Today, specialists might bury the whale, tow it out to sea, or cut it apart methodically.

But in 1970, the Oregon Highway Division was responsible for clearing the beach.

And they had a straightforward idea.

If rocks could be cleared with explosives, why not whale?

The logic was as follows:

-

Use enough dynamite.

-

Disintegrate the whale into small pieces.

-

Let scavengers — gulls, crabs, bacteria — handle the rest.

The plan had a certain rugged simplicity.

The execution did not.

The Decision: 20 Sticks of Dynamite

Officials decided on 20 cases of dynamite — about half a ton of explosives.

They placed the charges beneath the whale.

They calculated that the explosion would break the carcass into manageable chunks.

They instructed spectators to stand back — about a quarter mile away.

They believed that distance would be safe.

They did not fully account for the physics of whale blubber.

The Crowd Gathers

Word spread quickly.

People came to watch.

Television crews arrived.

Children climbed onto cars for a better view.

Locals brought cameras.

It felt less like a sanitation effort and more like a seaside spectacle.

The idea of blowing up a whale had a strange carnival quality to it.

No one anticipated what would happen next.

The Blast

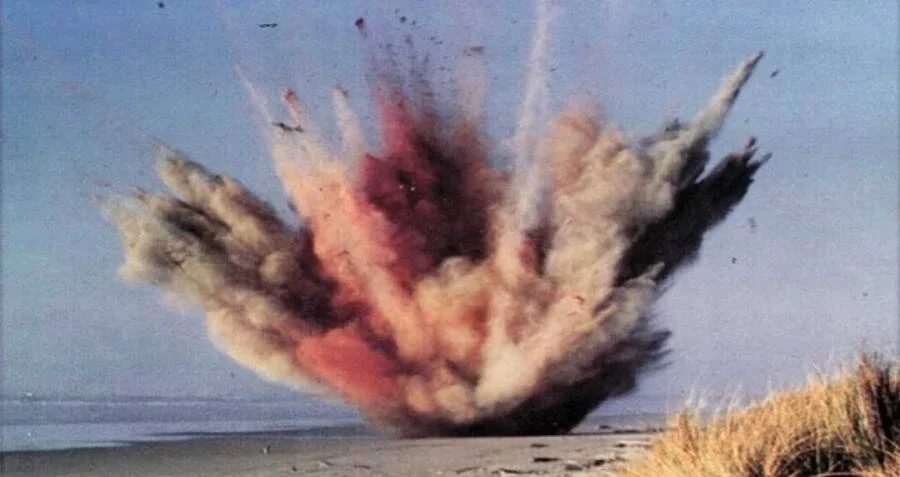

At approximately 3:45 p.m., the charges detonated.

The explosion thundered across the beach.

For a split second, it looked successful.

The whale disappeared into smoke and debris.

Then gravity intervened.

When the Blubber Fell

Chunks of whale did not disintegrate into fine mist.

They launched.

Massive slabs of blubber — some weighing hundreds of pounds — arced high into the air and began descending toward the stunned spectators.

Cars were crushed.

People ran.

The sky rained meat.

One particularly large piece landed directly on a brand-new Oldsmobile, flattening the roof.

Other chunks scattered across the beach, some landing dangerously close to onlookers.

Miraculously, no one was seriously injured.

But the beach was not cleared.

It was redecorated.

A Failure of Physics

The problem was simple in hindsight.

Whale blubber is dense and elastic.

When explosive force is applied beneath such a mass, the energy transfers upward — launching pieces like biological artillery shells.

Instead of pulverizing the carcass, the blast transformed it into projectiles.

Even worse, much of the whale remained largely intact.

The smell intensified.

The cleanup problem had multiplied.

The Aftermath

After the spectacle subsided, officials were left with:

-

A beach littered with whale fragments

-

Damaged vehicles

-

National embarrassment

The Highway Division eventually buried what remained of the whale.

Seagulls did indeed feast — but on far larger pieces than anyone had intended.

The incident was captured by local news reporter Paul Linnman, whose deadpan narration would later become iconic.

The footage circulated for years before becoming a viral sensation in the early days of the internet.

The Reporter Who Made It Immortal

Paul Linnman’s report included a line that would echo in pop culture history:

“The blast blasted blubber beyond all believable bounds.”

His calm, matter-of-fact delivery contrasted beautifully with the absurdity unfolding behind him.

The clip resurfaced decades later, becoming one of the earliest viral videos of the digital age.

Long before YouTube, the exploding whale became a cult legend.

Why Blow It Up?

The decision wasn’t entirely irrational.

Explosives had been used to clear obstacles in construction and demolition.

Officials believed fragmentation would reduce the whale to pieces small enough for scavengers to handle.

What they underestimated was scale.

Eight tons is not a boulder.

It is organic mass filled with gas and elasticity.

And explosives amplify unpredictability.

Nature’s Resistance to Simplification

The exploding whale incident highlights a broader truth:

Nature does not always cooperate with human efficiency.

We assume control.

We apply force.

We expect compliance.

But ecosystems are complex.

Bodies decompose on their own timeline.

Blubber does not obey neat equations.

Sometimes the simplest solution is patience.

Not the Only Whale Explosion

Interestingly, decomposing whales can explode naturally.

As internal gases build, pressure can rupture the skin.

There are documented cases of spontaneous whale explosions on beaches, though rarely at such theatrical scale.

In Florence, officials inadvertently accelerated a process nature might have completed — just with far more drama.

Bureaucracy and Confidence

The incident also reflects something timeless about bureaucracy.

Officials faced a problem.

They chose a decisive solution.

They trusted expertise.

But expertise without testing can become overconfidence.

The explosion was not malicious.

It was optimistic.

And optimism, when paired with dynamite, can be hazardous.

The Cultural Legacy

Today, the exploding whale is a beloved piece of Pacific Northwest folklore.

Florence even erected a small memorial plaque acknowledging the event.

The phrase “don’t dynamite the whale” has become shorthand for poorly thought-out solutions.

It is referenced in:

-

Environmental studies

-

Crisis management lectures

-

Internet humor archives

It survives because it is absurd — but also instructive.

Lessons from 1970

The Exploding Whale Incident teaches several enduring lessons:

-

Scale matters.

-

Public spectacle amplifies failure.

-

Nature resists simplification.

-

Not all problems require explosive solutions.

It also foreshadows something else — the modern era of viral embarrassment.

In 1970, only local viewers saw the footage.

Today, such an incident would dominate social media within minutes.

The Smell That Wouldn’t Die

Despite the blast, the stench persisted for days.

The buried remains continued to decompose.

In the end, the most effective solution was the least dramatic one:

Time.

Sometimes, time accomplishes what dynamite cannot.

Final Reflections: When Force Meets Folly

The exploding whale incident is funny.

It is chaotic.

It is messy.

It is absurd.

But it is also deeply human.

Faced with inconvenience, we often reach for decisive action.

We prefer dramatic solutions to patient ones.

In 1970, a dead whale became a spectacle because someone believed force was cleaner than decay.

Instead, the beach became a cautionary tale.

The whale exploded.

The blubber fell.

And history gained one of its strangest, most unforgettable lessons:

Not every problem needs a bigger blast.

Sometimes, you just let the tide handle it.