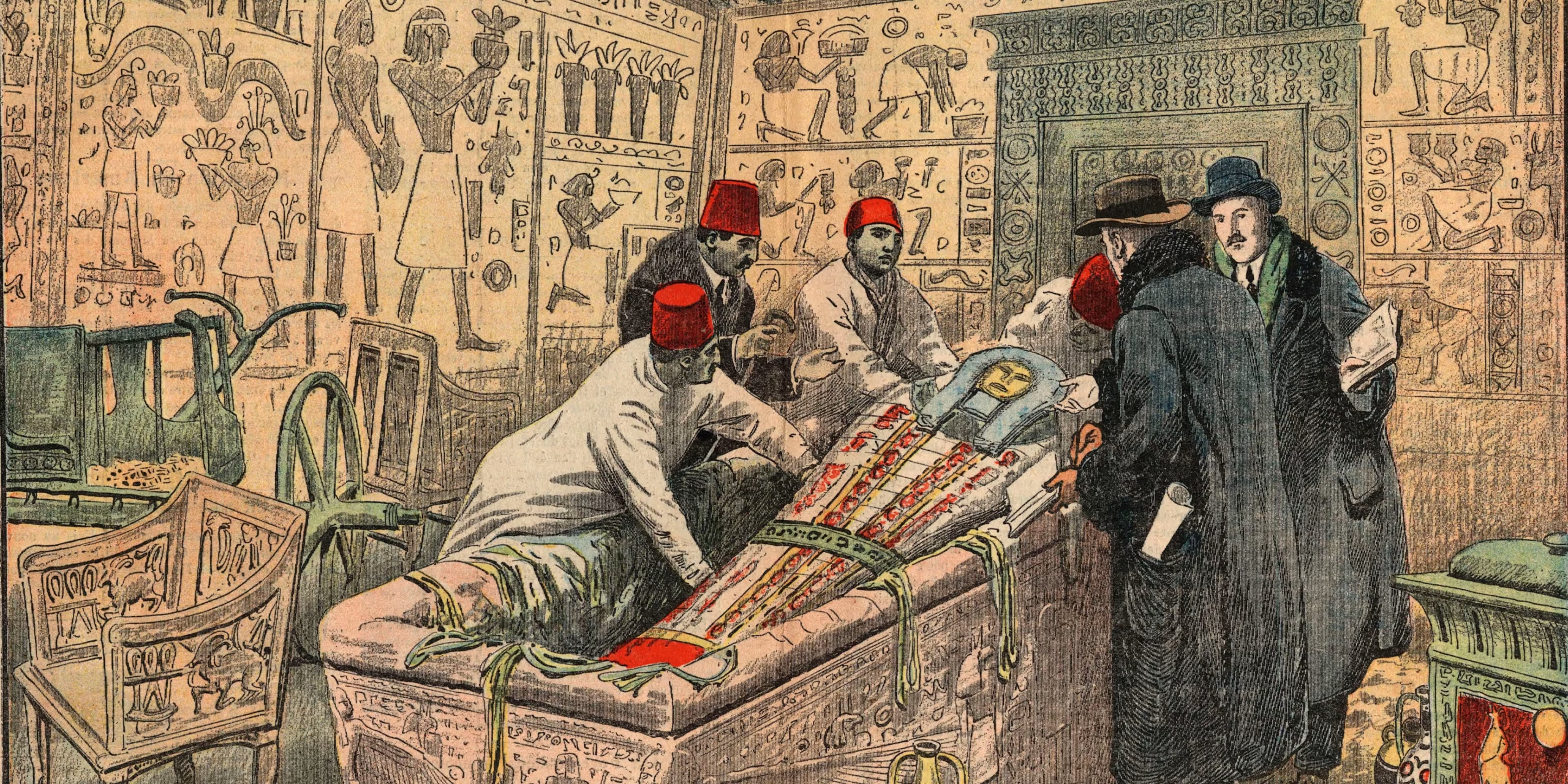

On November 26, 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter stood inside a narrow passageway carved into the limestone of Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Behind him, Lord Carnarvon and a small group of onlookers waited in tense silence. Carter had just chipped a small hole into a sealed doorway that had remained untouched for over 3,000 years. He held a candle up to peer inside. Carnarvon famously asked, “Can you see anything?” Carter replied, “Yes — wonderful things.”

On November 26, 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter stood inside a narrow passageway carved into the limestone of Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Behind him, Lord Carnarvon and a small group of onlookers waited in tense silence. Carter had just chipped a small hole into a sealed doorway that had remained untouched for over 3,000 years. He held a candle up to peer inside. Carnarvon famously asked, “Can you see anything?” Carter replied, “Yes — wonderful things.”

What Carter had uncovered was the tomb of Tutankhamun, a relatively obscure pharaoh of ancient Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. But the discovery would become far more than an archaeological triumph. Within months, whispers began to circulate. A wealthy patron dead. Strange illnesses. Sudden tragedies. Newspapers seized on the drama. Before long, the world was captivated not just by golden treasures and jeweled sarcophagi, but by something darker — the so-called Curse of Tutankhamun.

The idea that disturbing the resting place of the Boy King would unleash supernatural vengeance proved irresistible. It combined ancient mysticism, colonial ambition, and the glamour of 1920s media spectacle into one enduring legend. But how much of the curse was myth, how much was coincidence, and why has the story refused to die for more than a century?

The Tomb That Shouldn’t Have Existed

Tutankhamun ruled Egypt around 1332–1323 BCE. Unlike the towering figures of Ramses II or Akhenaten, Tut was a minor king, ascending the throne as a child and dying at around 19 years old. His reign was short and politically transitional. For centuries, his name faded into relative obscurity.

Yet it was precisely that obscurity that preserved him.

Most royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings had been plundered in antiquity. Grave robbers stripped gold and valuables, leaving little behind. But Tutankhamun’s tomb, tucked beneath debris from later excavations, remained largely intact. When Carter finally found it after years of fruitless searching, he uncovered one of the most astonishing archaeological discoveries in history.

Inside were over 5,000 artifacts: gilded shrines, chariots, ceremonial weapons, and the now-iconic golden burial mask. The world was stunned. Egyptology entered the popular imagination overnight.

And then the deaths began.

Lord Carnarvon’s Fate

In April 1923, just months after the tomb’s opening, Lord Carnarvon died in Cairo. The cause was blood poisoning following an infected mosquito bite, reportedly aggravated by a shaving cut. It was an unfortunate but medically explainable death.

Yet the timing was irresistible to journalists. Newspapers began hinting at an ancient curse placed upon the tomb to protect it from intruders. Some reports claimed that a warning inscription had been found reading, “Death shall come on swift wings to him who disturbs the peace of the king.” In reality, no such inscription was documented in Tutankhamun’s tomb.

But the legend was born.

Adding fuel to the fire were dramatic details: at the moment of Carnarvon’s death, Cairo’s lights reportedly went out. Back in England, his dog allegedly howled and dropped dead. Whether coincidence or embellishment, these details cemented the idea that something supernatural was at work.

Media Sensation and Egyptomania

The 1920s were a perfect breeding ground for a curse narrative. Spiritualism was popular. The trauma of World War I had left many people fascinated by death and the afterlife. Ancient Egypt, with its elaborate burial rituals and mummification practices, seemed mystical and otherworldly.

Newspapers competed fiercely for readership, and the idea of a pharaoh’s curse made for irresistible headlines. Sensational stories outsold sober archaeological reports.

Soon, every misfortune connected to the excavation was framed as evidence of the curse. Illnesses, accidents, even natural deaths years later were retroactively linked to Tutankhamun’s wrath.

Yet the facts tell a different story.

Separating Fact from Fiction

Howard Carter himself lived until 1939, nearly 17 years after opening the tomb. He died of lymphoma at age 64 — a respectable lifespan for the time. Many other members of the excavation team also lived long lives.

Statistical analyses conducted decades later found no unusual mortality rate among those present at the tomb’s opening. In fact, many of them outlived average life expectancy.

The so-called curse appeared selective and inconsistent.

However, a handful of early deaths did occur among people associated with the tomb, including Arthur Mace and George Jay Gould. These instances were heavily publicized, reinforcing the narrative.

The human mind is wired to detect patterns, especially when death and mystery are involved. Once the curse theory gained traction, every tragedy seemed to confirm it.

Scientific Theories

Though supernatural explanations dominate popular culture, some have proposed scientific possibilities behind the early illnesses.

One theory suggests that sealed tombs can contain mold spores or bacteria that become harmful when disturbed. Certain fungi, such as Aspergillus, can cause respiratory infections in people with weakened immune systems. It’s conceivable that exposure to ancient microbial environments contributed to some illnesses.

However, there’s no conclusive evidence linking specific pathogens in Tutankhamun’s tomb to the deaths in question. Most of the fatalities had clear medical explanations unrelated to mysterious toxins.

In short, science provides possibilities — but no definitive proof of a deadly curse.

Colonial Context and Cultural Anxiety

The curse narrative also reflects deeper cultural tensions.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb occurred during a period of British colonial influence in Egypt. For some observers, the idea of an ancient Egyptian king striking back at Western intruders carried symbolic weight. It was a reversal of power — the colonized past haunting the imperial present.

The curse story may have resonated because it tapped into subconscious guilt and anxiety about cultural appropriation and exploitation. Carter and Carnarvon were extracting priceless artifacts from an ancient civilization and shipping many of them abroad. The idea that the king might retaliate felt poetic.

In that sense, the curse became more than a spooky tale. It became a narrative about justice, however fantastical.

Hollywood and the Undead Pharaoh

By the 1930s, the curse legend had fully entered popular culture. Universal Studios released The Mummy in 1932, starring Boris Karloff as an undead Egyptian priest. While not directly about Tutankhamun, the film drew heavily from the fevered fascination surrounding the tomb’s discovery.

From there, the trope of the cursed mummy became a staple of horror fiction. Countless films, books, and television episodes riffed on the idea of ancient retribution.

The golden mask of Tutankhamun became an icon — instantly recognizable and perpetually linked to danger and mystique.

The curse story had transcended its historical roots. It was now myth.

Why the Legend Endures

The Curse of Tutankhamun endures because it sits at the intersection of fact and fantasy. There really was a spectacular discovery. There really were deaths. The mystery lies in the interpretation.

Humans are drawn to stories that imbue events with meaning. Random misfortune feels unsatisfying. A curse feels dramatic and purposeful.

The tomb itself, filled with glittering treasures meant to accompany a king into eternity, reinforces the aura of sacredness. Ancient Egyptians placed great emphasis on protecting the dead. Their tomb inscriptions sometimes warned of divine punishment for desecration. Even if Tutankhamun’s tomb lacked a specific curse inscription, the broader cultural context makes the idea plausible.

And then there’s the romance of it all — a boy king, a hidden chamber, flickering candlelight revealing gold untouched for millennia. Add sudden death, and the narrative practically writes itself.

The Real Tutankhamun

Ironically, the curse narrative often overshadows the historical Tutankhamun himself. Modern studies, including CT scans and DNA analysis, suggest he may have suffered from various health issues, possibly including malaria and a broken leg that became infected.

He was not a mighty warrior pharaoh but a teenager navigating political restoration after his predecessor’s controversial religious reforms.

In death, however, he achieved a kind of immortality no conqueror could rival. The curse legend, true or not, ensured his name would never fade again.

A Legend Without Teeth

More than a century after the tomb’s discovery, there is no credible evidence that Tutankhamun’s spirit struck down those who disturbed his rest. The deaths associated with the excavation were tragic but explainable.

Yet the legend persists.

Perhaps because it reminds us that the past still has power. That ancient civilizations were not inert relics but living cultures with beliefs about death and eternity. The idea of a curse may not be scientifically sound, but it reflects a respect — even a fear — of disturbing what was meant to remain sacred.

In the end, the Curse of Tutankhamun says less about ancient Egypt and more about us. About our fascination with mystery. About our need to weave stories from coincidence. About the uneasy relationship between exploration and reverence.

Howard Carter saw “wonderful things” when he peered into the tomb. What followed was equally wonderful and strange — a tale of gold, glory, and ghosts that refuses to fade.

The Boy King never sought revenge. But in capturing the world’s imagination, he achieved something more enduring than any curse: eternal intrigue.