In the late 19th century, America had a complicated relationship with medicine.

In the late 19th century, America had a complicated relationship with medicine.

There were no federal drug laws. No warning labels. No FDA. Pharmacies sold tonics promising vigor, nerve strength, sexual vitality, and relief from “melancholia.” Opium was common. Morphine was respected. Cocaine was considered modern.

And in 1886, a pharmacist in Atlanta created a syrup that would become the most recognizable beverage on Earth.

It contained coca leaf extract.

It contained caffeine.

And yes—it originally contained cocaine.

This is the story of how Coca-Cola was born in an age of patent medicines, how cocaine became part of its formula, and how shifting science, politics, and public fear transformed both the drug and the drink.

America’s Gilded Age Drug Culture

To understand how cocaine ended up in a soft drink, you must understand the era.

In the 1880s:

-

Cocaine was legal.

-

It was used in medicine as a local anesthetic.

-

Sigmund Freud praised it in academic papers.

-

It was marketed as a cure for morphine addiction.

There was little public awareness of addiction risk. Cocaine was associated with energy, clarity, and modern science.

It was exotic—derived from the South American coca plant.

It was fashionable.

It was profitable.

And it was everywhere.

Enter John Stith Pemberton

The inventor of Coca-Cola was John Stith Pemberton, a Confederate veteran and pharmacist in Atlanta.

Pemberton was wounded during the Civil War and, like many veterans, became dependent on morphine for pain relief. Searching for alternatives, he began experimenting with tonics and stimulants.

In 1885, he created a beverage called “French Wine Coca,” inspired by European coca wines that combined coca leaf and alcohol.

Then came Prohibition—at least locally. Atlanta banned alcohol in 1886.

Pemberton reformulated.

He removed the wine.

He kept the coca.

He added kola nut (for caffeine).

Coca-Cola was born.

What Was in Early Coca-Cola?

The original Coca-Cola syrup included:

-

Extract of coca leaves (which contained cocaine)

-

Kola nut extract (source of caffeine)

-

Sugar syrup

-

Flavorings (vanilla, citrus oils, etc.)

The amount of cocaine per serving was small—estimated at around 9 milligrams in early formulations. That’s significantly lower than recreational doses, but not insignificant.

At the time, it wasn’t scandalous.

It was a selling point.

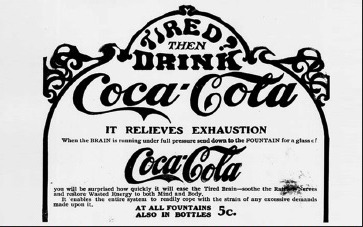

Marketing the Miracle Tonic

Early advertisements described Coca-Cola as:

-

A cure for headaches

-

A remedy for fatigue

-

A “brain tonic”

-

A temperance drink alternative

It was sold at soda fountains in pharmacies for five cents a glass.

The name itself advertised its ingredients: coca + kola.

There was no attempt to hide the coca content.

In fact, it suggested modernity and vitality.

The Rise of Cocaine Panic

By the 1890s, public perception began to shift.

Medical literature increasingly acknowledged cocaine’s addictive potential. Sensationalized newspaper stories linked cocaine to crime, particularly in racist narratives targeting Black communities in the American South.

The drug that had once symbolized innovation now symbolized danger.

Coca-Cola’s success grew just as cocaine’s reputation darkened.

This posed a problem.

Asa Candler Takes Over

After Pemberton’s death in 1888, businessman Asa Candler acquired control of Coca-Cola.

Candler was a marketing genius. He transformed the drink from a regional curiosity into a national brand.

But he was also pragmatic.

As anti-cocaine sentiment grew, he began reducing the coca content in the formula.

By the early 1900s, Coca-Cola used “spent” coca leaves—leaves with most of the cocaine removed.

Eventually, the company eliminated active cocaine entirely.

The 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act

The turning point came with federal regulation.

In 1906, the U.S. passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, requiring accurate labeling and regulating certain substances.

The era of unregulated patent medicines was ending.

Coca-Cola adapted quickly.

The cocaine was effectively gone from the beverage by 1904–1905, though coca leaf extract—minus the active alkaloid—remained part of the flavoring process.

A Legal Loophole and a Unique Supplier

Even today, Coca-Cola still uses coca leaf extract in its formula.

But here’s the twist:

The company sources decocainized coca leaves from a licensed facility in the United States. The cocaine is extracted and sold legally for medical use as a topical anesthetic.

The remaining flavoring is used in the beverage.

It’s one of the few legal coca processing operations in America.

The legacy lives on—just without the stimulant.

Did Coca-Cola Make People High?

Not in the way modern imagination suggests.

The cocaine content in early Coca-Cola was mild, especially when diluted in soda water. A typical recreational line of cocaine today can contain far more.

Still, the combination of:

-

Cocaine

-

Caffeine

-

Sugar

Created a noticeable stimulant effect.

The drink energized people.

That energy helped build a brand.

The Broader Patent Medicine Era

Coca-Cola was hardly alone.

Other products of the era included:

-

Cocaine toothache drops for children

-

Heroin cough syrup

-

Opium-based pain relievers

The boundary between medicine and beverage was porous.

The difference between “tonic” and “soft drink” was marketing.

Coca-Cola survived because it evolved with the law.

Many competitors did not.

The Power of Branding

One of Coca-Cola’s greatest strengths was its ability to shift identity.

It moved from:

Medicinal tonic → Refreshing soda

Drug-associated drink → Family beverage

Regional syrup → Global symbol

By the 1920s, Coca-Cola was no longer a stimulant cure.

It was Americana.

The cocaine origin faded into trivia.

Myth vs. Reality

Modern retellings sometimes exaggerate the story.

No, people weren’t buying Coca-Cola as a cocaine delivery system.

No, it wasn’t a 19th-century nightclub drug in a glass.

But yes—it contained a measurable amount of cocaine.

Yes—it was marketed as energizing medicine.

Yes—it rode the wave of a drug craze before distancing itself.

The truth is more subtle—and more interesting—than myth.

Cocaine’s Fall from Grace

By the early 20th century, cocaine became heavily regulated.

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 restricted cocaine and opiate distribution.

Public opinion hardened.

Criminalization expanded.

The drug’s reputation shifted from medicine to menace.

Coca-Cola had already pivoted.

Its survival depended on adaptation.

Cultural Irony

There’s something profoundly ironic about Coca-Cola’s origin.

A product once infused with cocaine became:

-

A symbol of wholesome family life

-

A staple of children’s birthday parties

-

A patriotic emblem during World War II

The stimulant disappeared.

The brand endured.

The Evolution of Ingredients

While cocaine vanished, caffeine remained.

Coca-Cola continued to market itself as refreshing and energizing—just without the legal risk.

The stimulant profile shifted from narcotic to socially accepted.

Today, caffeine is ubiquitous and normalized.

In 1886, cocaine was too.

History changes what is considered dangerous.

A Lesson in Regulation and Reinvention

Coca-Cola’s early cocaine content reflects a broader pattern:

Innovation often precedes regulation.

New substances are embraced.

Risks emerge.

Society adjusts.

The company’s ability to evolve saved it.

Others—less flexible—disappeared.

Final Reflections: From Drugstore to Global Icon

The story of Coca-Cola containing cocaine is not just a curiosity.

It’s a snapshot of a transitional America:

-

A nation without drug laws

-

A culture fascinated by modern chemistry

-

A marketplace where medicine and marketing intertwined

Coca-Cola began as a patent medicine in a pharmacy.

It survived scandal, regulation, and cultural shift.

It shed its narcotic origin and became something else entirely.

Today, when you open a bottle, you taste sugar, carbonation, and caffeine.

But buried in its history is a reminder of an era when the line between refreshment and remedy was thin—and when one of the world’s most famous brands was born in a cloud of coca leaves and optimism.

History doesn’t always change all at once.

Sometimes it fizzes quietly in a glass.