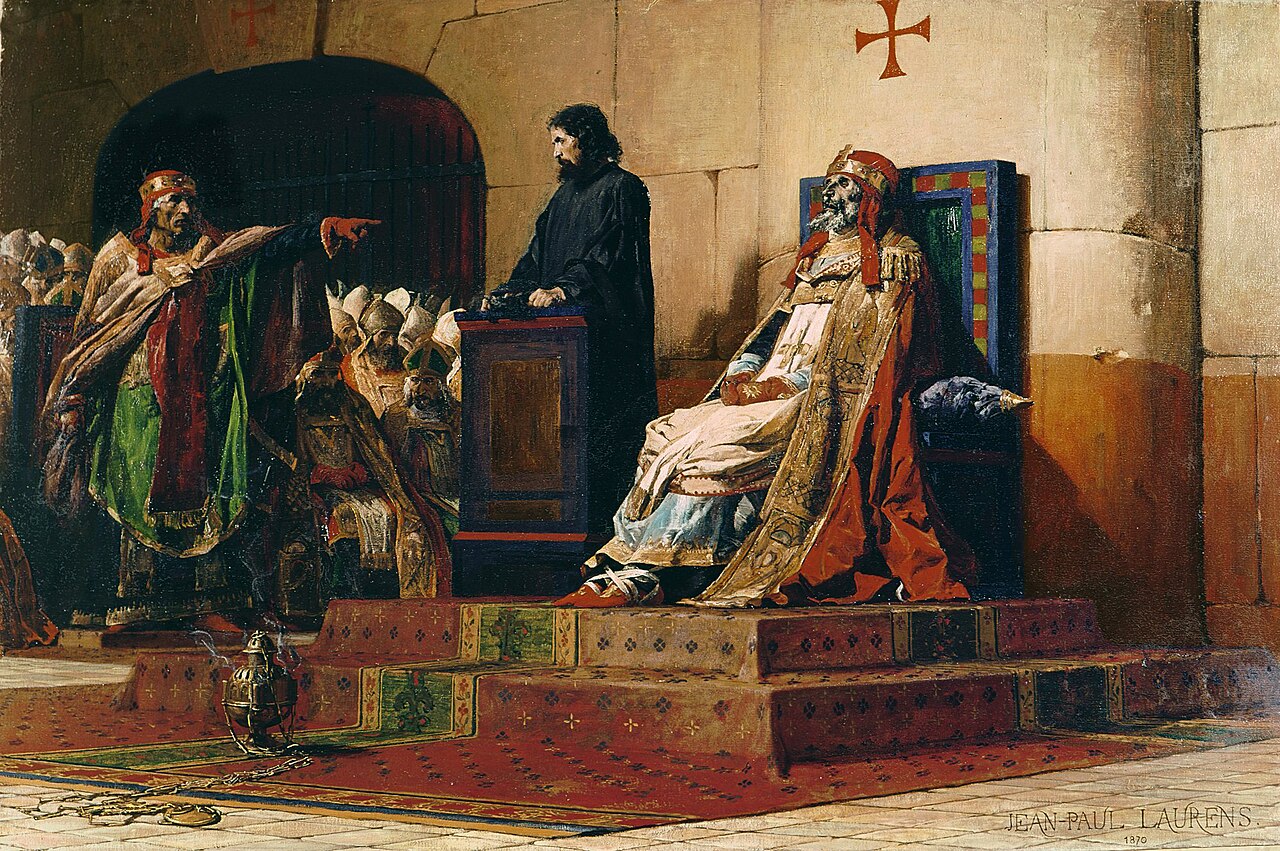

In January of 897 AD, the Catholic Church staged a legal proceeding so bizarre that it still feels unreal more than a thousand years later. A corpse—rotted, dressed in papal robes, propped up on a throne—was placed on trial before clergy, nobles, and citizens of Rome. The accused could not speak. A deacon answered on his behalf. The judge was the current pope. The charges were crimes allegedly committed years earlier.

In January of 897 AD, the Catholic Church staged a legal proceeding so bizarre that it still feels unreal more than a thousand years later. A corpse—rotted, dressed in papal robes, propped up on a throne—was placed on trial before clergy, nobles, and citizens of Rome. The accused could not speak. A deacon answered on his behalf. The judge was the current pope. The charges were crimes allegedly committed years earlier.

The defendant was Pope Formosus, dead for nine months.

This event, known as The Cadaver Synod or Synodus Horrenda (“The Horrifying Synod”), was not madness for madness’ sake. It was the grotesque endpoint of political rivalry, factional violence, and a church that had become deeply entangled with imperial power.

It was a trial meant not to discover truth, but to annihilate a legacy—even if that meant dragging a corpse out of the grave.

Rome in the Late 9th Century: Chaos in the Holy City

To understand how the Cadaver Synod happened, you must understand Rome in the late 800s.

This was not the serene, unified Church people imagine today. It was a battlefield.

The papacy was weak.

Rome was controlled by violent aristocratic factions.

Popes were made and unmade by political families.

Assassination, exile, and imprisonment were common papal outcomes.

The office of pope was not merely spiritual—it was a prize in an ongoing power struggle between Rome’s noble houses and the fading authority of the Carolingian Empire.

Into this chaos stepped Pope Formosus.

Who Was Pope Formosus?

Formosus was elected pope in 891 AD, but his troubles began long before that.

He was:

-

A skilled diplomat

-

Deeply involved in European power politics

-

Closely aligned with certain Frankish factions

As bishop of Porto, Formosus had traveled widely and gained influence—but also enemies.

One of those enemies was Pope John VIII, who accused Formosus of:

-

Abandoning his diocese

-

Aspiring to the papacy illegally

-

Conspiring against Rome

Formosus was excommunicated and forced to swear an oath never to return to Rome or seek high office again.

He eventually returned anyway.

Politics shifted. Enemies fell. Oaths were ignored.

Rome moved on.

Formosus Becomes Pope — and Makes Powerful Enemies

Once elected pope, Formosus faced a critical choice: whom to support as Holy Roman Emperor.

Two rival claimants emerged:

-

Arnulf of Carinthia, a German king

-

Lambert of Spoleto, backed by the powerful Spoletan family

Formosus sided with Arnulf.

This decision sealed his fate.

Arnulf invaded Italy, was crowned emperor by Formosus in Rome, and then suffered a sudden stroke—leaving Italy unstable and the Spoletan faction furious.

Formosus died shortly afterward in April 896.

His enemies had not forgotten.

Enter Pope Stephen VI: A Man with a Grudge

Formosus was succeeded by Pope Boniface VI, who lasted only two weeks. Then came Pope Stephen VI.

Stephen was aligned with the Spoletan faction—the very group Formosus had opposed.

To them, Formosus wasn’t just a political enemy.

He was a traitor.

And death was not enough.

Exhuming the Pope

Nine months after Formosus’ burial, Stephen VI ordered the unthinkable.

Formosus’ body was dug up from its tomb.

The corpse was already decomposed.

It was dressed in papal vestments.

Placed on a throne in the Lateran Basilica.

Propped upright like a grotesque marionette.

A deacon stood beside the corpse to answer questions on its behalf.

Rome gathered to watch.

The Charges Against a Corpse

Stephen VI presided as both judge and accuser.

Formosus was charged with:

-

Perjury

-

Violating canon law by holding multiple offices

-

Illegally ascending to the papacy

These were not theological issues. They were political weapons.

The verdict was predetermined.

The Trial Itself: A Theater of Hatred

Contemporary accounts describe Stephen VI screaming at the corpse.

He shook his fist.

He shouted accusations.

He demanded answers from a dead man.

The deacon’s responses were submissive, scripted, and futile.

Formosus was found guilty.

Sentence and Punishment

The punishment went beyond symbolic condemnation.

Stephen VI ordered:

-

All of Formosus’ papal acts annulled

-

All ordinations he performed declared invalid

-

The corpse stripped of papal vestments

Then came the most chilling act.

The three fingers Formosus used to give blessings were cut off.

The body was dragged through the streets of Rome.

Finally, it was thrown into the Tiber River.

The message was clear: Formosus was to be erased from history.

Rome Reacts — and Revolts

The Cadaver Synod horrified Rome.

Even in a brutal era, this crossed a line.

People whispered that the city was cursed.

Earthquakes struck Rome soon after.

Rumors spread that Formosus’ body had washed ashore and was performing miracles.

Public outrage exploded.

Stephen VI was arrested.

Imprisoned.

Strangled in his cell later that year.

The Aftermath: Undoing the Unthinkable

Subsequent popes quickly reversed the verdict.

Pope Theodore II retrieved Formosus’ body and reburied it with honor.

Pope John IX formally annulled the Cadaver Synod and banned trials of the dead.

For a brief moment, sanity returned.

But Rome would never forget what it had witnessed.

Why the Cadaver Synod Happened

This wasn’t madness—it was politics weaponized through religion.

The papacy was:

-

Vulnerable

-

Politicized

-

Controlled by factions

The trial was about:

-

Invalidating Formosus’ decisions

-

Undermining rival claims to power

-

Rewriting history

The corpse was a prop.

Psychological Horror and Power

What makes the Cadaver Synod so disturbing is not just its grotesque imagery, but what it reveals about power.

When institutions become obsessed with legitimacy, they will:

-

Rewrite the past

-

Destroy symbols

-

Desecrate even the dead

The trial wasn’t about Formosus.

It was about control.

The Church’s Dark Mirror

The Cadaver Synod stands as a warning.

It shows what happens when:

-

Spiritual authority becomes political currency

-

Leaders fear loss of legitimacy more than moral collapse

-

Institutions turn inward and devour themselves

The Church would eventually reform.

But this moment remains a scar.

Legacy: A Thousand Years of Shock

Few events in church history unsettle people like the Cadaver Synod.

It’s been:

-

Referenced in literature

-

Used as a cautionary tale

-

Remembered as the papacy’s lowest point

Not because it was violent—but because it was pointless cruelty wrapped in ritual.

Final Thoughts: When the Dead Are Not Left Alone

The Cadaver Synod reminds us that history’s greatest horrors don’t always involve armies or plagues.

Sometimes they happen in silence.

In robes.

In a courtroom where the accused cannot speak.

When power becomes afraid of memory, it will dig up the dead to silence them.

Even if it has to put a corpse on trial to do it.