In the summer of 1456, Europe looked up — and saw a warning written in fire.

In the summer of 1456, Europe looked up — and saw a warning written in fire.

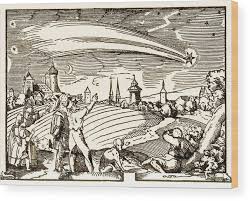

A blazing comet burned across the sky for weeks, its long tail stretching ominously over cities already trembling with fear. To many, it did not appear as a celestial object. It appeared as a sword. A flaming scythe. A divine omen.

The Ottoman Empire had just captured Constantinople three years earlier. Turkish forces were advancing into Europe. Christendom felt surrounded. Preachers warned of apocalypse. Plague still haunted memory. War was constant.

And then the comet arrived.

According to a story that has survived for centuries, Pope Callixtus III excommunicated the comet — formally condemning it as a tool of evil and ordering prayers against it.

The image is irresistible: a pontiff, seated in Rome, anathematizing a celestial body streaking across the heavens.

Did it really happen?

Not exactly.

But the myth — and the fear behind it — reveal far more about medieval psychology, cosmic superstition, and the relationship between faith and science than the literal truth ever could.

Europe in 1456: A Continent on Edge

The mid-15th century was not a calm era.

In 1453, Constantinople — the last remnant of the Byzantine Empire — fell to Sultan Mehmed II. The event shocked Christian Europe. The Ottomans now controlled a key gateway between East and West. Their armies were pressing into Hungary and the Balkans.

The idea that Islam might advance deeper into Europe felt real and immediate.

Religious anxiety surged.

The Church responded with calls to prayer, crusade, and unity. Europe was primed to interpret every unusual sign as a message from God — or from the devil.

And then came the comet.

The Return of Halley’s Comet

The comet that terrified Europe in 1456 was what we now know as Halley’s Comet.

At the time, comets were not understood scientifically. They were not predictable, recurring celestial bodies with orbital paths. They were erratic visitors — appearing without warning, blazing across the sky, and vanishing again.

Halley’s Comet was especially bright in 1456.

Chroniclers described it as:

-

A flaming sword

-

A torch carried across the sky

-

A tail stretching nearly halfway across the heavens

For people living in a worldview shaped by biblical imagery, such a sight demanded interpretation.

Comets as Omens

In medieval Europe, comets were almost universally interpreted as omens.

They foretold:

-

War

-

Plague

-

Famine

-

The death of kings

Even educated clergy accepted the idea that celestial phenomena signaled divine will.

The appearance of the 1456 comet coincided almost exactly with Ottoman military campaigns in Hungary. Turkish forces laid siege to Belgrade that summer.

The comet hung in the sky as cannons roared on the frontier.

To many, it seemed like a heavenly endorsement of Islamic conquest — or a divine warning of Christian failure.

Pope Callixtus III’s Response

Pope Callixtus III, a Spanish-born pontiff deeply concerned about Ottoman expansion, was already urging Christians to pray for victory against the Turks.

In June 1456, he issued a papal bull calling for special prayers and the ringing of church bells at noon to rally Christendom spiritually against the Ottoman threat.

This decree — calling for prayer against the Turks — would later become tangled with the comet.

Because the comet appeared at the same time.

And because medieval minds sought connection.

The Myth of Excommunication

Over time, a story emerged that Pope Callixtus III had formally excommunicated the comet.

The idea that a pope had condemned a celestial object was too good to resist. It fit neatly into stereotypes of medieval superstition and religious overreach.

But historians have found no contemporary record of an official papal decree excommunicating the comet.

What did happen was subtler:

-

The Pope ordered prayers against the Turkish advance.

-

The comet appeared simultaneously.

-

People assumed connection.

Later writers, particularly during the Enlightenment, exaggerated the story to mock medieval ignorance.

Voltaire, among others, helped popularize the tale as evidence of clerical absurdity.

The myth stuck.

Why the Story Persisted

The idea of excommunicating a comet survives because it’s symbolically powerful.

It represents:

-

Religion confronting nature

-

Authority attempting to command the cosmos

-

Faith colliding with astronomical ignorance

But the truth is less dramatic and more revealing.

The Pope didn’t curse the comet.

He prayed against the Ottoman army.

The sky and the battlefield simply overlapped in timing.

The Siege of Belgrade

While the comet blazed overhead, the Siege of Belgrade reached its climax.

Hungarian forces under John Hunyadi successfully repelled the Ottoman army in July 1456.

The victory was celebrated across Europe.

The Pope’s call for noon bells — originally intended to rally prayer during the siege — evolved into the Angelus bell tradition still practiced today.

In hindsight, the comet was retroactively interpreted by some as a sign of Christian triumph rather than doom.

Meaning shifted with outcome.

Science vs. Superstition

By the time Edmond Halley calculated the comet’s periodic orbit in 1705, demonstrating that the comet of 1456 was the same one seen in 1682 and predicted for 1758, the intellectual climate had changed.

Comets became predictable.

They lost their supernatural aura.

But in 1456, the cosmos still felt intimate.

The sky was not distant and mechanistic.

It was active.

It spoke.

The Psychology of Omen

When societies face existential threats, they seek signs.

In 1456:

-

The Ottoman Empire was expanding.

-

Christendom felt under siege.

-

Political unity was fragile.

The comet became a canvas for collective anxiety.

It wasn’t about astronomy.

It was about fear.

Enlightenment Mockery

Centuries later, Enlightenment thinkers ridiculed the idea of a pope excommunicating a comet.

They used it as shorthand for medieval backwardness.

But modern historians caution against oversimplification.

Medieval clergy were not ignorant of astronomy.

Universities taught celestial mechanics according to Aristotelian cosmology.

The Church sponsored scientific inquiry in many areas.

The excommunication story became exaggerated polemic rather than documented event.

What the Pope Actually Did

Primary sources show that Callixtus III issued a bull on June 29, 1456, ordering special prayers and fasting for the Christian defense against the Turks.

There is no language condemning the comet itself.

But because the comet appeared during those weeks, chroniclers and later writers fused the two events.

The myth grew.

The Power of Narrative

Why does the idea of excommunicating a comet endure?

Because it feels poetic.

A medieval pope raising his hand against the sky.

The Church confronting cosmic fire.

Faith battling astronomy.

It captures the tension between worldview and reality.

Even if it didn’t happen literally, it speaks to something true about the era.

The Comet’s Indifference

Halley’s Comet did not slow.

It did not respond to prayer.

It did not alter its orbit.

It passed as it always does — returning roughly every 76 years.

In 1456, it inspired fear.

In 1910, it inspired curiosity.

In 1986, it inspired spacecraft missions.

Human interpretation changed.

The comet did not.

Final Reflections: When the Sky Feels Personal

The story of the Pope excommunicating a comet is more myth than documented fact.

But the fear behind it was real.

In 1456, Europe saw a blazing sign in the sky and interpreted it through the lens of war and survival.

The Pope called for prayer against earthly enemies.

Later generations misremembered that prayer as a curse against the heavens.

The tale endures because it reminds us of something timeless:

When the world feels unstable, we look upward.

We search for meaning in fire and light.

We imagine that someone, somewhere, must be in control.

Even if that means raising a hand and condemning a comet.

The sky burns.

Empires tremble.

And history leaves behind stories that glow almost as brightly as the stars themselves.