What if nearly three centuries of the Middle Ages were fabricated?

What if nearly three centuries of the Middle Ages were fabricated?

What if the year 1000 was never really the year 1000 — but closer to 700? What if Charlemagne never existed? What if cathedrals, kings, and entire dynasties were inserted into the historical record as part of a grand deception?

This is the premise of the Phantom Time Hypothesis — one of the strangest and most audacious historical conspiracy theories ever proposed.

Unlike fringe theories that orbit ancient aliens or secret societies, the Phantom Time Hypothesis focuses on something deceptively simple: the calendar.

According to its supporters, approximately 297 years — specifically the period between 614 and 911 AD — were artificially added to history. The early Middle Ages, they claim, are partly or entirely fictional.

It sounds absurd.

But it has persisted for decades.

The Origin of the Theory

The Phantom Time Hypothesis was first proposed in 1991 by German historian and publisher Heribert Illig.

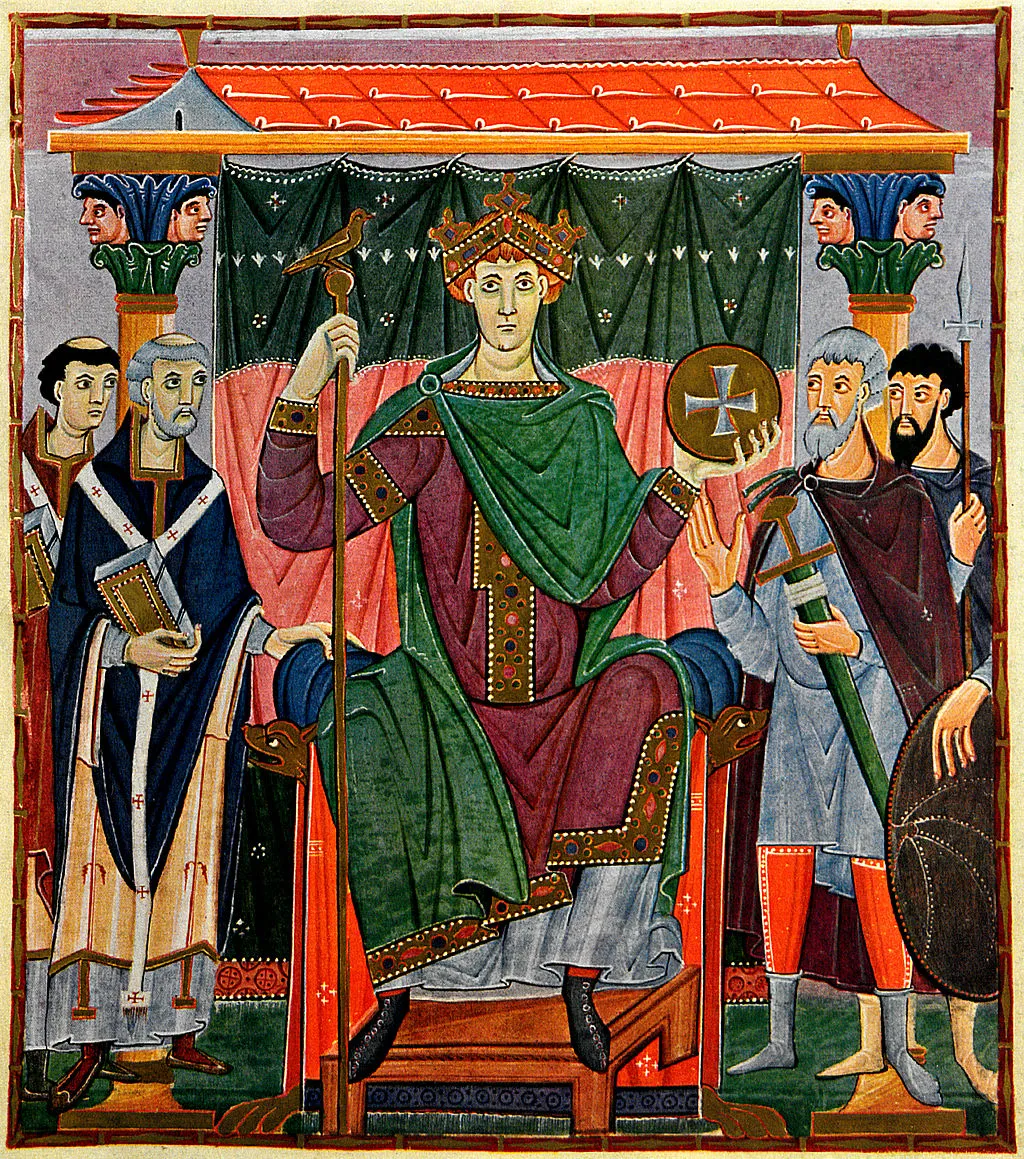

Illig argued that Holy Roman Emperor Otto III and Pope Sylvester II conspired in the late 10th century to manipulate the calendar. According to the theory, they inserted nearly 300 phantom years into history to position themselves symbolically at the year 1000 — a powerful, millennial milestone.

Illig suggested that this fabrication also retroactively glorified the reign of Charlemagne, the great Frankish king crowned in 800 AD.

If those centuries were invented, then Charlemagne’s empire — and much of early medieval European history — might be a fiction.

It was a bold claim.

And one that historians immediately rejected.

The Calendar Confusion Argument

At the heart of the theory is a misunderstanding — or reinterpretation — of calendar systems.

Illig focused on the shift from the Julian calendar (introduced by Julius Caesar) to the Gregorian calendar (introduced in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII). When the Gregorian calendar was adopted, ten days were skipped to correct accumulated drift.

Illig argued that the correction should have been 13 days, not 10. The discrepancy, he claimed, proved that roughly 300 years had been artificially added to the timeline.

In his view, the missing three days represented centuries that never occurred.

It is an elegant-sounding argument.

It is also incorrect.

The Gregorian reform corrected the calendar back to its alignment with the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD — not to the time of Julius Caesar. When calculated properly, the ten-day adjustment was accurate.

The supposed mathematical proof collapses under scrutiny.

The Case Against Charlemagne

One of the most provocative elements of the Phantom Time Hypothesis is its challenge to the existence of Charlemagne.

Charlemagne — crowned Emperor of the Romans in 800 AD — is a towering figure in European history. He unified much of Western Europe, reformed education, and laid foundations for the Holy Roman Empire.

According to Illig, Charlemagne was a literary construct — a glorified figure invented to legitimize later rulers.

If nearly three centuries were fabricated, Charlemagne’s reign would fall squarely within that phantom period.

But dismantling Charlemagne requires more than calendar arithmetic.

It would mean dismissing extensive documentation, archaeological evidence, coinage, architectural remains, and cross-referenced records from Byzantine and Islamic sources.

It would mean asserting that multiple independent civilizations coordinated a false narrative — without leaving any trace of conspiracy.

Archaeology vs. Phantom Time

One of the strongest counters to the Phantom Time Hypothesis is archaeology.

Material culture does not easily cooperate with calendar manipulation.

Buildings, burial sites, carbon-dated remains, dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), and stratigraphy all provide independent lines of evidence for continuous development during the alleged phantom period.

For example, dendrochronology allows scientists to match tree-ring patterns across centuries with remarkable precision. Timber used in medieval buildings can be dated accurately to specific years.

If nearly 300 years were missing, tree-ring chronologies would show a glaring gap.

They do not.

Similarly, Islamic and Chinese records document events in Europe during the same period Illig claims was fabricated. For the theory to hold, these cultures would need to have inserted matching phantom centuries into their own histories — an implausible level of coordination.

The Appeal of the Theory

Despite overwhelming scholarly rejection, the Phantom Time Hypothesis persists.

Why?

Because it taps into a powerful psychological appeal.

It suggests that history is malleable. That authority can manipulate time itself. That what we accept as ancient truth may be constructed illusion.

It also offers a kind of intellectual thrill — the idea that one person has uncovered a grand deception overlooked by generations of scholars.

Conspiracy theories often thrive on this dynamic. They invert expertise. They transform skepticism into superiority.

The Phantom Time Hypothesis presents itself as bold revisionism — a challenge to academic complacency.

But bold does not mean correct.

The Problem of Synchronization

One of the fatal weaknesses of the theory lies in global synchronization.

By the 7th to 10th centuries, Europe was not isolated. Trade routes connected it to the Byzantine Empire, the Islamic Caliphates, and even distant China.

Astronomical events such as eclipses were recorded across civilizations. These celestial events can be retroactively calculated with precision.

If 297 years had been inserted, eclipse records would not align across cultures.

Yet they do.

Historical eclipses recorded in European chronicles match modern astronomical calculations.

Time, it turns out, leaves fingerprints in the sky.

The Byzantine and Islamic Records

The Byzantine Empire maintained meticulous records of emperors, wars, and church councils. The Islamic world, during its Golden Age, documented interactions with European territories.

For the Phantom Time Hypothesis to be true, Byzantine and Islamic historians would need to have participated in the fabrication — or independently invented the same phantom centuries.

There is no evidence of such coordination.

The same applies to numismatics. Coins minted during the supposed phantom period exist in abundance. Their metallurgy, inscriptions, and distribution align with gradual historical development.

You cannot insert centuries without leaving seams.

And scholars see none.

Why the Theory Won’t Die

The Phantom Time Hypothesis endures for the same reason many fringe theories endure: it challenges consensus in dramatic fashion.

It also exploits a genuine truth — that early medieval records are sparse compared to later centuries. The so-called “Dark Ages” are less documented than the Renaissance.

Sparse documentation can create space for doubt.

But absence of abundant records is not evidence of fabrication.

Historians rely on cross-disciplinary evidence — archaeology, climate data, linguistics, art history — not just written chronicles.

When all those lines converge, the case becomes strong.

The Internet Age and Revival

In the early 1990s, Illig’s theory circulated mostly within German-language publications. With the rise of the internet, it found new audiences.

Online forums and video platforms amplified it. The idea that “we are living in the wrong year” proved irresistible to some.

It pairs well with other calendar-based conspiracies — such as claims that the Gregorian calendar is flawed beyond correction.

But in academic circles, the hypothesis has never gained traction.

It remains a fringe curiosity.

A Thought Experiment in Historical Trust

Even if the Phantom Time Hypothesis fails as scholarship, it raises an interesting philosophical question:

How do we know what we know about the past?

History is not memory. It is reconstruction — built from fragments, artifacts, and interpretation.

Trust in historical chronology rests on cumulative evidence. When multiple independent methods align, confidence increases.

The Phantom Time Hypothesis collapses not because historians dismiss it out of hand, but because the evidence across disciplines contradicts it.

Carbon dating does not show a 300-year anomaly. Tree rings do not skip centuries. Astronomical records align.

Time leaves traces.

And those traces are consistent.

The Human Fascination with Lost Time

There is something inherently compelling about the idea of missing years.

Stories of lost civilizations and erased empires capture imagination. The Phantom Time Hypothesis reframes that fascination into a calendar-based mystery.

What if entire generations never existed? What if medieval Europe was shorter than we think?

It feels like a glitch in reality.

But historical evidence suggests continuity, not collapse.

The early Middle Ages were complex and transformative — the rise of the Carolingians, the spread of monasticism, Viking expansions, the shaping of European kingdoms.

Erasing nearly 300 years would unravel countless interconnected developments.

The tapestry would not hold.

Why It Matters

At first glance, the Phantom Time Hypothesis seems harmless — a quirky idea about calendars.

But it intersects with broader issues about trust in expertise and historical literacy.

If large swaths of documented history can be dismissed without evidence, then the foundation of historical understanding weakens.

Skepticism is healthy.

But skepticism without rigorous evidence becomes speculation.

The strength of history lies in method — cross-checking, peer review, interdisciplinary validation.

The Phantom Time Hypothesis does not withstand that process.

Conclusion: Time That Wasn’t Lost

The Phantom Time Hypothesis is audacious. It challenges centuries of scholarship with a simple claim: nearly 300 years never happened.

It proposes that emperors manipulated chronology to crown themselves in a symbolic year. That Charlemagne might be fiction. That the early Middle Ages are padded with invented time.

But when tested against archaeology, astronomy, and global records, the theory collapses.

The years between 614 and 911 AD were real. They were messy, transformative, and imperfectly documented — but they were lived.

The appeal of phantom time reflects a deeper human curiosity about how we measure existence. Calendars feel authoritative, yet arbitrary. Years tick forward whether or not we understand them.

In the end, the Phantom Time Hypothesis tells us less about missing centuries and more about modern doubt.

Time was not stolen.

It passed, as it always does — quietly, persistently, leaving evidence in stone, in soil, and in the stars.