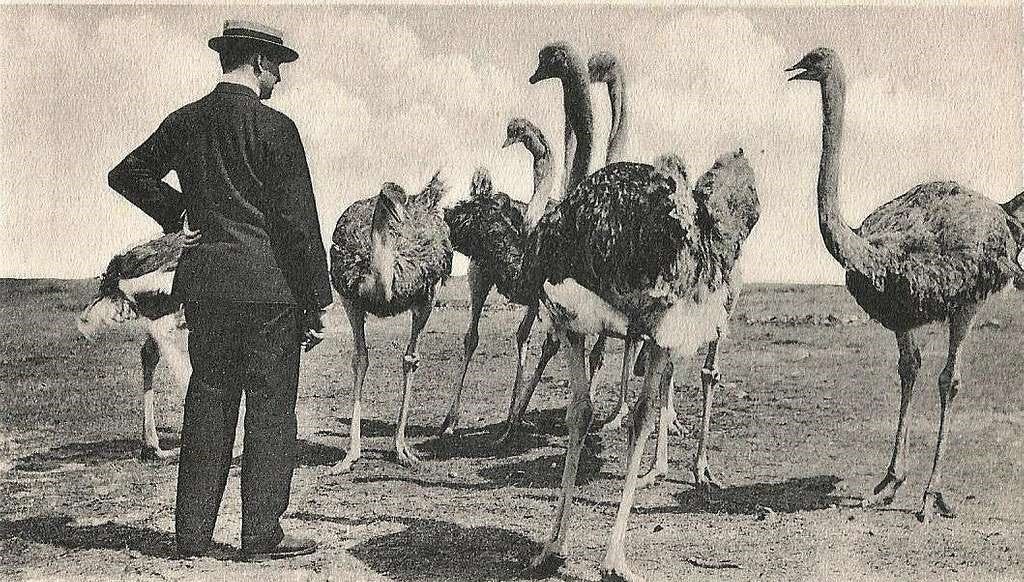

In the long, colorful history of military conflicts, few episodes are as strange, humbling, or darkly hilarious as The Great Emu War of 1932. It’s a real event—officially sanctioned by the Australian government—where soldiers armed with machine guns were deployed against… emus. Not metaphorical emus. Not code-named emus. Actual, six-foot-tall, flightless birds with legs like pistons and brains seemingly hardwired for chaos.

In the long, colorful history of military conflicts, few episodes are as strange, humbling, or darkly hilarious as The Great Emu War of 1932. It’s a real event—officially sanctioned by the Australian government—where soldiers armed with machine guns were deployed against… emus. Not metaphorical emus. Not code-named emus. Actual, six-foot-tall, flightless birds with legs like pistons and brains seemingly hardwired for chaos.

What followed was a month-long campaign that ended not with victory parades or medals of honor, but with parliamentary embarrassment, international ridicule, and a grudging acknowledgment that the emus had won.

This is the story of how it happened, why it happened, and what it revealed about nature, warfare, and humanity’s eternal habit of underestimating anything that looks goofy until it’s sprinting toward you at 30 miles per hour.

Australia in the Early 1930s: Drought, Depression, and Desperation

To understand why a modern government would deploy soldiers against birds, you have to understand Australia in 1932.

The country was deep in the Great Depression. Farmers—particularly wheat farmers in Western Australia—were barely surviving. Many were World War I veterans who had been given land under a government settlement scheme, encouraged to farm marginal soil with limited resources.

The land was harsh. Rainfall was unreliable. The soil was unforgiving. And then came the emus.

Enter the Emus: An Unlikely Enemy

Emus are native to Australia and, under normal circumstances, mostly mind their own business. But 1932 was not a normal year.

After a long drought, around 20,000 emus migrated inland toward the wheat belt near Campion, Walgoolan, and Chandler. What they found were freshly planted crops, reliable water sources, and very little standing between them and an all-you-can-eat buffet.

The birds trampled fences, destroyed wheat fields, and created gaps that allowed rabbits to swarm in behind them. Farmers watched entire seasons disappear in days.

Attempts to scare them off failed. Emus ignored humans, shrugged off small arms fire, and returned the moment people turned their backs.

So the farmers did what any desperate group might do in 1932 Australia: they asked the government for help.

The Government’s Solution: Call in the Army

The request eventually reached Minister of Defence Sir George Pearce, who approved a military response. The reasoning was simple:

-

Soldiers already knew how to use machine guns

-

Ammunition was cheaper than compensation

-

It would be a “good training exercise”

And so, in November 1932, the Australian Army was mobilized against the emus.

This is the moment where history quietly clears its throat and says, “You sure about this?”

The Forces Involved

The military commitment was modest but official:

-

Major G.P.W. Meredith in command

-

Two soldiers under his direct leadership

-

Two Lewis machine guns

-

10,000 rounds of ammunition

On paper, it seemed absurdly one-sided. Lewis guns were proven weapons in World War I—capable of firing hundreds of rounds per minute. Emus, meanwhile, did not have guns, tanks, or even a known chain of command.

And yet.

Phase One: The Birds Do Not Cooperate

The first engagement took place near Campion in early November. Soldiers attempted to ambush a group of emus near a dam.

The plan failed almost immediately.

The birds scattered in every direction, moving far faster than anticipated. The machine guns jammed after only a few shots. When the guns were operational, emus proved remarkably hard to hit.

They didn’t cluster.

They didn’t panic.

They didn’t run in straight lines.

They dispersed like trained guerrilla fighters.

Meredith later remarked that emus seemed capable of absorbing multiple hits and continuing to run, leading to rumors—likely exaggerated, but telling—that some birds survived direct machine-gun fire.

The body count after the first skirmishes was embarrassingly low.

The Mounted Gun Disaster

In a moment that feels lifted from slapstick cinema, the army attempted a new tactic: mounting a machine gun on a truck to chase down the emus.

It did not go well.

The terrain was rough, the birds were fast, and firing a machine gun from a bouncing vehicle turned out to be wildly impractical. The gunner couldn’t maintain aim, the truck struggled to keep up, and the emus simply outmaneuvered the vehicle with contemptuous ease.

The plan was abandoned.

At this point, the emus were not just winning—they were humiliating the army.

The Press Gets Involved

News of the operation spread quickly, and Australian newspapers had a field day.

Headlines mocked the campaign.

Cartoons depicted emus wearing medals.

Editorials questioned why the army couldn’t defeat birds that couldn’t even fly.

One journalist famously suggested that if Australia ever went to war against humans again, they should recruit emus instead.

Public opinion shifted from mild curiosity to outright ridicule.

Phase Two: Persistence Without Progress

Despite early failures, the campaign continued through November. Soldiers managed to kill several hundred emus—estimates range from 200 to 1,000—but at a massive cost in ammunition and morale.

The numbers told the story:

-

Thousands of rounds fired

-

Hundreds of birds killed

-

Tens of thousands remained

The emus adapted. They split into smaller groups, making them even harder to target. Meredith later described them as having a kind of “organized resistance,” though that may have been gallows humor more than tactical analysis.

Still, the perception was unavoidable: this was not working.

The End of the War

By December 1932, political pressure mounted. Questions were raised in Parliament. Was this really the best use of military resources during an economic crisis?

Sir George Pearce quietly withdrew the troops.

There was no victory announcement.

No official declaration of defeat.

Just a slow, awkward fade-out.

The emus remained.

Who Actually Won?

By any reasonable measure, the emus won the war.

They:

-

Continued to inhabit the wheat belt

-

Maintained their migration patterns

-

Forced the government to abandon military solutions

The farmers, meanwhile, were left with damaged crops and shattered expectations.

Eventually, the government implemented bounty systems and improved fencing—methods that proved far more effective than machine guns ever were.

Nature, it turned out, responds better to patience than bullets.

Why the Emu War Matters (Yes, Really)

It’s easy to dismiss the Great Emu War as a historical joke—and it absolutely is funny—but it also offers surprisingly relevant lessons.

1. Technology Doesn’t Guarantee Control

Military hardware designed for human warfare does not automatically solve environmental problems. You can’t brute-force ecosystems without consequences—or embarrassment.

2. Nature Adapts Faster Than You Expect

The emus didn’t need strategy meetings or command structures. Their natural behavior—speed, dispersion, resilience—made them unbeatable under the circumstances.

3. Governments Panic Too

Desperate times lead to desperate solutions. The Emu War is what happens when political optics override practical thinking.

The Emu’s Unexpected Legacy

Today, the Great Emu War has achieved cult status.

It’s taught in classrooms.

Referenced in memes.

Featured in documentaries and comedy specials.

The emu itself has become an ironic symbol of resistance—an animal that accidentally humbled a modern military.

Some historians argue that the story’s endurance comes from its relatability. It’s not about heroism or villainy. It’s about overconfidence meeting reality.

And losing.

Australia’s National Bird, Redeemed

There’s an added layer of irony: the emu appears on Australia’s coat of arms, alongside the kangaroo. Both animals were chosen because they cannot easily walk backward, symbolizing national progress.

After 1932, the emu earned its place in a different way—not as a symbol of progress, but as a reminder of humility.

Final Thoughts: When History Winks at You

The Great Emu War sits at the intersection of tragedy, comedy, and cautionary tale. It’s a moment when history seems to wink at us and say, “You thought you had this under control. You did not.”

No matter how advanced we become, no matter how confident our plans, there will always be something—nature, chance, or a large, angry bird—that refuses to cooperate.

And sometimes, the smartest thing you can do isn’t escalate.

It’s admit defeat, build a better fence, and let the emus be emus.