On the morning of August 6, 1945, Tsutomu Yamaguchi stepped off a streetcar in Hiroshima and walked toward the Mitsubishi shipyard where he was on temporary assignment.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Tsutomu Yamaguchi stepped off a streetcar in Hiroshima and walked toward the Mitsubishi shipyard where he was on temporary assignment.

He had three months left in his business trip.

He was tired.

He missed his wife.

He missed his infant son.

Then the sky split open.

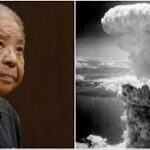

A flash brighter than anything he had ever seen consumed the city. Heat tore through the air. Buildings vaporized. Shadows burned into stone. The first atomic bomb used in war—code-named Little Boy—detonated over Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m.

Yamaguchi was less than two miles from the hypocenter.

He survived.

Three days later, after returning home to Nagasaki to recover from his burns, he walked into his office and began describing the horror to his supervisor.

Then the sky split open again.

This is the story of the only man officially recognized by Japan as having survived both atomic bombings—a story of coincidence so improbable it borders on myth, and survival so fragile it feels like defiance against physics itself.

Hiroshima: August 6, 1945

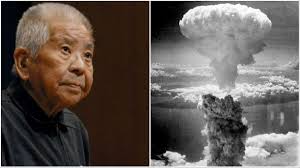

Tsutomu Yamaguchi was 29 years old, an engineer working for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. He had spent months in Hiroshima helping design oil tankers for the war effort.

On that Monday morning, he realized he had forgotten his personal seal—a stamp necessary for official paperwork—and turned back toward his lodgings.

That small decision altered everything.

At 8:15 a.m., the Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb from approximately 31,000 feet.

The explosion released energy equivalent to about 15 kilotons of TNT.

Yamaguchi later described seeing a flash—“like the magnesium flare of a photographer’s camera, but far brighter.”

He threw himself into a ditch just as the blast wave hit.

The shockwave ruptured his eardrums.

The heat burned the upper half of his body.

The force lifted and slammed him.

Around him, Hiroshima disintegrated.

A City Erased

Within seconds:

-

Temperatures near the hypocenter reached thousands of degrees.

-

Wooden homes ignited instantly.

-

Concrete buildings collapsed.

-

Human beings were incinerated where they stood.

An estimated 70,000–80,000 people died instantly.

By the end of 1945, the toll would rise to approximately 140,000.

Yamaguchi staggered through a landscape that no longer resembled a city.

People wandered, skin hanging in strips.

Water boiled in rivers clogged with bodies.

Smoke blackened the sky.

He found shelter in an air-raid bunker that night.

He did not yet understand radiation.

He only knew the world had ended.

The Decision to Go Home

Despite severe burns, Yamaguchi resolved to return to his family in Nagasaki.

Transportation was chaotic, but the rail lines—astonishingly—began operating again within days.

On August 7, bandaged and feverish, he boarded a train.

He traveled through a wounded Japan, unaware that another bomb was already en route.

Nagasaki: August 9, 1945

Back in Nagasaki, Yamaguchi reunited with his wife Hisako and their infant son, Katsutoshi.

His wife had survived a conventional bombing raid months earlier.

They believed the worst was behind them.

On August 9, Yamaguchi reported to work despite his injuries.

He began telling his supervisor about Hiroshima.

His boss was skeptical.

“One bomb cannot destroy a city,” he reportedly said.

At 11:02 a.m., the second atomic bomb—Fat Man—detonated over Nagasaki.

Yamaguchi was inside an office building approximately two miles from the blast center.

The building shielded him from the full force.

But once again, the world exploded.

Twice Targeted, Twice Alive

The Nagasaki bomb was even more powerful than the one dropped on Hiroshima—approximately 21 kilotons.

Another city was obliterated.

Between 35,000 and 40,000 people died instantly. Tens of thousands more would perish from injuries and radiation sickness.

Yamaguchi survived again.

His home was destroyed.

His family miraculously lived.

His burns worsened.

His hair fell out.

Radiation sickness ravaged his body in the following weeks.

But he endured.

Living as a Hibakusha

Survivors of the atomic bombings are known in Japan as hibakusha.

They carried more than physical scars.

They faced stigma.

Many feared hibakusha were contagious.

Others believed they were genetically damaged.

Employment discrimination was common.

Marriage prospects suffered.

Yamaguchi rarely spoke publicly about his experiences for decades.

Like many survivors, he chose quiet survival over spectacle.

The Science of Survival

How did he live?

Several factors likely contributed:

-

Distance from the hypocenters.

-

Physical shielding (ditches, concrete buildings).

-

Luck—an immeasurable but undeniable element.

Radiation exposure depends heavily on proximity, shielding, and time spent in contaminated zones.

Yamaguchi’s burns were severe but not immediately fatal.

His radiation dose, while high, was survivable.

His survival does not minimize the horror.

It underscores the randomness of it.

Recognition at Last

For decades, Yamaguchi was known locally as a double survivor.

But it wasn’t until 2009—64 years after the bombings—that the Japanese government officially recognized him as a nijū hibakusha, a double-affected survivor.

He was 93 years old.

He had lived nearly a full lifetime after standing beneath two atomic suns.

Speaking Out

In his later years, Yamaguchi became an outspoken advocate for nuclear disarmament.

He addressed the United Nations in 2006.

He described the bombs not as weapons of war but as weapons of indiscriminate destruction.

He said:

“I cannot understand why the world cannot understand the agony of the atomic bomb.”

He carried scars on his skin.

But the deeper wound was moral.

The Mythic Quality of Survival

There is something almost mythological about surviving one atomic bombing, let alone two.

Yet Yamaguchi’s story reminds us:

Atomic weapons are not abstractions.

They are not numbers.

They are not policy points.

They are flashes of light that erase cities.

And survival, in that context, is not triumph.

It is accident.

The Broader Context

Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only two instances of nuclear weapons used in warfare.

Their bombings precipitated Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945.

World War II ended.

The nuclear age began.

The bombs were justified by some as necessary to prevent greater casualties from invasion.

Critics argue they introduced a weapon whose destructive capacity dwarfed moral reasoning.

Yamaguchi lived in the shadow of that debate.

A Life Beyond the Bombs

Despite lifelong health complications, Yamaguchi:

-

Worked as an engineer.

-

Raised children.

-

Lived into his 90s.

-

Wrote poetry about the bombings.

He refused to be defined solely by survival.

But the bombs defined history.

Radiation’s Long Shadow

Survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki experienced elevated rates of:

-

Leukemia

-

Solid cancers

-

Cataracts

-

Chronic illness

Research on hibakusha shaped modern understanding of radiation exposure.

Their suffering became data—necessary, clinical, sobering.

Yamaguchi’s body was part of that scientific record.

The Fragility of Civilization

The atomic bombings revealed something terrifying:

A single device could erase a city in seconds.

Yamaguchi experienced that revelation twice.

He saw two urban landscapes dissolve.

He walked through two infernos.

He heard two shocks that changed the world.

Final Reflections: The Man Who Should Not Have Lived

Tsutomu Yamaguchi died in 2010 at the age of 93.

He outlived empires.

He outlived the war.

He outlived the era that created the bomb.

His life is not a miracle in the divine sense.

It is a reminder of probability.

When weapons are built that can erase cities, survival becomes statistical.

Yamaguchi beat the odds twice.

But his story is not about luck.

It is about warning.

He saw what nuclear fire does.

He lived long enough to tell us.

The question he leaves behind is simple:

Will we listen?