On June 15, 1859, on a mist-covered island in the Pacific Northwest, an American farmer raised his rifle and shot a pig.

On June 15, 1859, on a mist-covered island in the Pacific Northwest, an American farmer raised his rifle and shot a pig.

The pig had been rooting in his potato patch—again.

It belonged to a British employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The bullet killed the animal instantly.

Within weeks, warships arrived.

Marines landed.

Artillery faced artillery across a narrow stretch of water.

The United States and Great Britain—two global powers—stood on the brink of armed conflict.

All because of a pig.

This was The Pig War, one of the strangest military standoffs in modern history—a confrontation that revealed how fragile borders can be, how pride can escalate trivial disputes, and how cooler heads sometimes barely prevent catastrophe.

A Border Drawn in Ambiguity

To understand the Pig War, you have to go back to diplomacy.

In 1846, the United States and Great Britain signed the Oregon Treaty, settling a long-standing dispute over the Pacific Northwest. The treaty declared that the border would follow the 49th parallel westward “to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island.”

The problem?

There wasn’t just one channel.

Between Vancouver Island (British territory) and the U.S. mainland lay a maze of waterways—Haro Strait, Rosario Strait, and others—surrounding the San Juan Islands.

Both sides interpreted “the middle of the channel” differently.

Both claimed the islands.

The treaty’s vagueness planted a seed of future conflict.

San Juan Island: A Quiet Tension

For years after the treaty, the San Juan Islands remained sparsely populated.

But gradually, settlers arrived.

-

American farmers moved in from Washington Territory.

-

The British Hudson’s Bay Company established sheep farms.

The Americans saw themselves as citizens of an expanding republic.

The British saw themselves as stewards of imperial land.

The tension simmered quietly.

Until a pig wandered into a potato field.

The Pig That Crossed a Line

The pig belonged to Charles Griffin, an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

It was a large, black pig that frequently roamed freely.

The farmer whose potatoes it favored was Lyman Cutlar, an American settler.

On June 15, 1859, after catching the pig eating his crops yet again, Cutlar had enough.

He shot it.

Griffin demanded compensation—$100.

Cutlar offered $10.

Neither man would yield.

It was a small dispute.

But in contested territory, small disputes carry weight.

Pride Enters the Field

Word of the incident spread among American settlers.

They feared British retaliation or eviction.

They petitioned American authorities for protection.

Meanwhile, British officials insisted American settlers were trespassing on British soil.

In July 1859, American Brigadier General William S. Harney dispatched U.S. troops to San Juan Island.

About 66 American soldiers landed under Captain George Pickett—the same Pickett who would later lead the ill-fated charge at Gettysburg.

The American flag was raised.

The British were not amused.

Warships in the Strait

Britain responded swiftly.

Royal Navy ships sailed into the waters around the island.

At one point, five British warships faced off against a handful of American troops and cannons.

The British had overwhelming naval superiority.

The Americans had dug in defensively.

Cannons were aimed.

Fuses were ready.

Tempers were high.

All because of a pig.

A Dangerous Escalation

The standoff escalated rapidly.

British Rear Admiral Robert Baynes had orders to assert British sovereignty—but not to start a war.

American General Harney was aggressive and eager to assert U.S. claims.

Neither side wanted to appear weak.

The situation was volatile.

A single misfire could have triggered full-scale war between two nations that had fought just decades earlier in the War of 1812.

Cooler Heads Prevail

Fortunately, not everyone wanted bloodshed.

Admiral Baynes reportedly refused to fire the first shot over “a squabble about a pig.”

Diplomatic channels activated.

The U.S. government, wary of conflict with Britain while tensions simmered elsewhere, sought de-escalation.

By October 1859, both sides agreed to a joint military occupation of San Juan Island.

Each would station a small force.

Neither would fire.

Neither would concede sovereignty.

The Pig War became a tense peace.

Twelve Years of Armed Patience

Remarkably, the joint occupation lasted 12 years.

American soldiers camped on the southern end of the island.

British Royal Marines camped on the northern end.

They interacted occasionally—sometimes amicably.

No shots were fired in anger.

The pig remained the only casualty.

Life settled into a strange coexistence.

Two flags flew.

Two military forces stood guard.

One island waited for resolution.

Arbitration at Last

In 1871, the Treaty of Washington addressed several disputes between the United States and Great Britain.

The San Juan question was submitted to arbitration.

Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany was chosen as neutral arbitrator.

After reviewing arguments from both sides, the decision came in 1872:

The border would follow Haro Strait.

The San Juan Islands belonged to the United States.

The British withdrew peacefully.

The Pig War ended without a single battle.

The Real Causes Behind the Comedy

It’s tempting to treat the Pig War as pure absurdity.

But beneath the humor were serious geopolitical dynamics:

-

Ambiguous treaty language.

-

Expanding American territorial ambition.

-

British imperial presence in North America.

-

Military commanders eager to assert authority.

The pig was the spark.

The tinder was already dry.

The Fragility of Borders

The Pig War reveals something timeless:

Borders drawn on paper are only as stable as the clarity behind them.

When language is vague, interpretation becomes political.

And when politics meets pride, escalation follows.

In 1859, the Pacific Northwest was not yet the quiet, defined border we know today.

It was a question mark.

The pig wandered into that question.

The Human Element

Lyman Cutlar likely never imagined his frustration would escalate internationally.

Charles Griffin likely wanted fair compensation.

Neither intended war.

But in contested territory, even routine conflicts acquire symbolic weight.

A potato patch became a battlefield.

A Model of Peaceful Resolution

Despite the tension, the Pig War is often cited as a rare success story in conflict de-escalation.

Why?

-

Military leaders exercised restraint.

-

Governments prioritized diplomacy.

-

Arbitration was accepted.

In an era when wars frequently erupted over pride and territory, the San Juan dispute ended peacefully.

It set a precedent for international arbitration.

What If It Had Gone Differently?

Had Admiral Baynes fired his cannons…

Had General Harney escalated further…

The United States and Great Britain might have entered open war.

Given global alliances and imperial commitments, the consequences could have rippled worldwide.

History pivoted on restraint.

Memory and Legacy

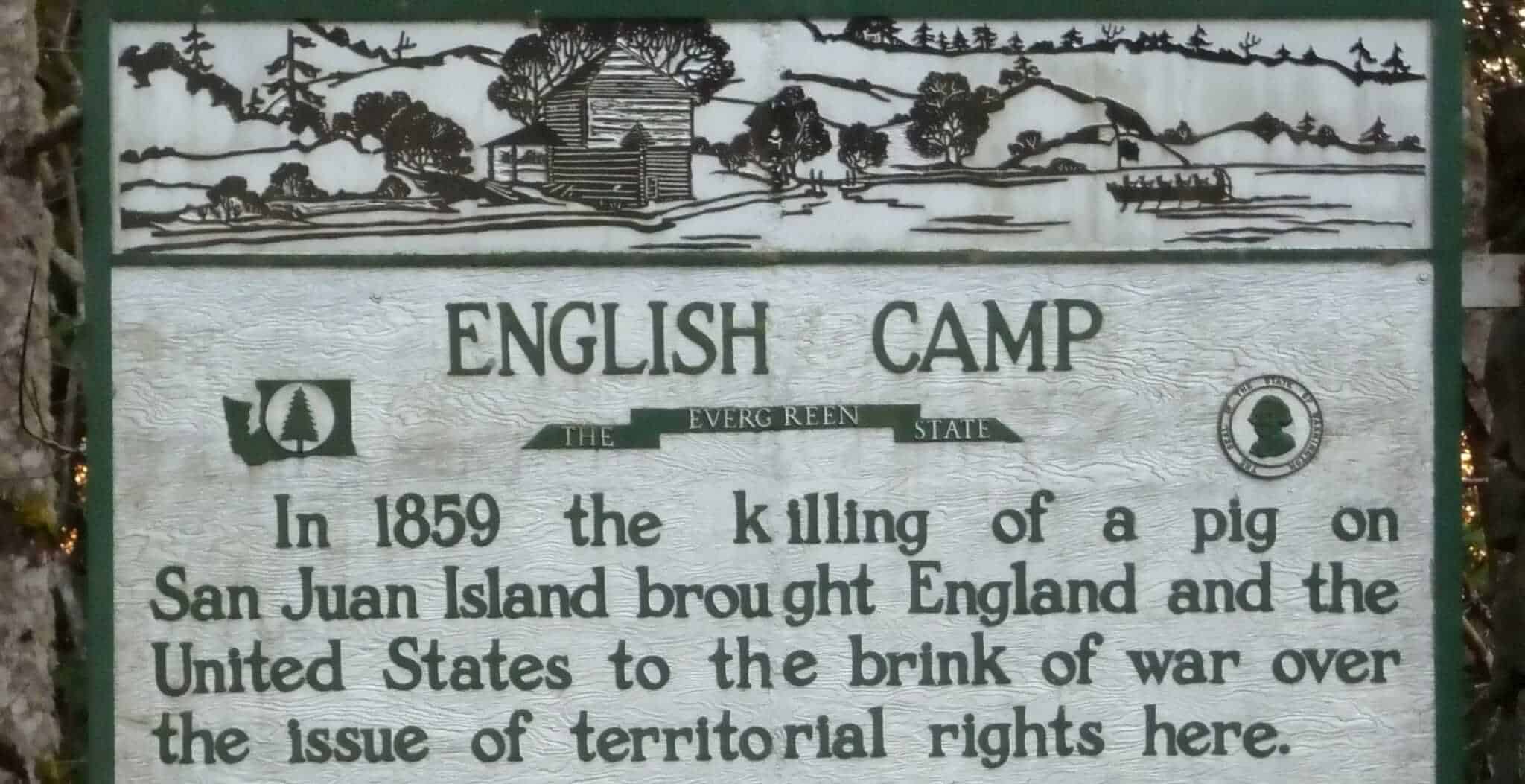

Today, San Juan Island is tranquil.

Historic sites mark both American and British camps.

Tourists visit.

The pig is commemorated in plaques and storytelling.

The island stands as a quiet reminder that not all near-wars become wars.

Final Reflections: The Shot That Didn’t Echo

The Pig War is a story of absurd beginnings and measured endings.

It reminds us that:

-

Pride can inflate minor incidents.

-

Ambiguity breeds conflict.

-

Restraint matters.

One pig died.

No humans did.

In a century filled with bloody conflicts, that outcome feels almost miraculous.

The pig wandered into a potato patch.

An empire almost answered with cannon fire.

Instead, diplomacy prevailed.

Sometimes, history is shaped not by the battles fought—but by the battles avoided.